Recently, Felix Salmon, Clusterstock, and others have been mentioning an essay from the Hoover Institute about the financial crisis. Now, I haven’t yet linked to the essay in question… I will, but only after I’ve said some thing about it.

I was on the front lines of the securitization boom. I saw everything that happened and am intimately familiar with how one particular bank, and more generally familiar with many banks’, approach to these businesses. I think that there are no words that adequately describes how utterly stupid it is that there is still a “debate” going on surrounding banks and their roles in the financial crisis. There are no unknowns. People have been blogging, writing, and talking about what happened ad naseum. It’s part of the public record. Whomever the author of this essay is (I’m sure I’ll be berated for not knowing him like I was for not knowing Santelli — a complete idiot who has no place in a public conversation whose requisites are either truth or the least amount of intellectual heft), unless it’s writing was an excesses in theoretical reasoning about a parallel universe, it’s a sure sign they don’t what they are talking about that they make some of the points in the essay. Let’s start taking it apart so we can all get on with our day.

For instance, it isn’t true that Wall Street made these mortgage securities just to dump them on them the proverbial greater fool, or that the disaster was wrought by Wall Street firms irresponsibly selling investment products they knew or should have known were destined to blow up. On the contrary, Merrill Lynch retained a great portion of the subprime mortgage securities for its own portfolio (it ended up selling some to a hedge fund for 22 cents on the dollar). Citigroup retained vast holdings in its so-called structured investment vehicles. Holdings of these securities, in funds in which their own employees personally participated, brought down Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers. AIG, once one of the world’s most admired corporations, made perhaps the biggest bet of all, writing insurance contracts against the potential default of these products.

So Wall Street can hardly be accused of failing to eat its own dog food. It did not peddle to others an investment product that it was unwilling to consume in vast quantities itself.

(Emphasis mine.)

Initial premise fail. I had a hard time finding the part to emphasize since it’s all so utterly and completely wrong. Since I saw everything firsthand, let me be unequivocal about my remarks: the entire point of the securitization business was to sell risk. I challenge anyone to find an employee of a bank who says otherwise. This claim, that “it isn’t true that Wall Street made these mortgage securities just to dump them on them the proverbial greater fool” is proven totally false. There’s a reason the biggest losers in this past downturn were the biggest winners in the “league tables” for years running. As a matter of fact, there’s a reason that league tables, and not some other measure, were a yardstick for success in the first place! League tables track transaction volume–do I really need to point out that one doesn’t judge themselves by transaction volume when their goal isn’t to merely sell/transact?

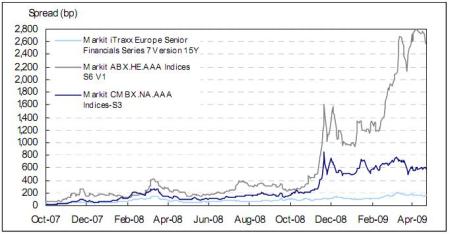

In fact, the magnitude of writedowns by the very firms mentioned (Merrill and Citi) relative to the original value of these investments imply that a vast, vast majority of the holdings were or were derived from the more shoddily underwritten mortgages underwritten in late 2006, 2007, and early 2008. In fact, looking at ABX trading levels, as of yesterday’s closing, shows the relative quality of these mortgages and makes my point. AAA’s from 2007 (series 1 and 2) trading for 25-26 cents on the dollar and AAA’s from early 2006 trading at roughly 67 cents on the dollar. The relative levels are what’s important. Why would Merrill be selling it’s product for 22 cents on the dollar if the market level is so much higher (obviously the sale occurred a few months ago, but the “zip code” is still the same)? This is a great piece of evidence that banks are merely left holding the crap they couldn’t sell when the music stopped.

Now, onto the next stop on the “How wrong can you get it?” tour.

It isn’t true, either, that Wall Street manufactured these securities as a purblind bet that home prices only go up. The securitizations had been explicitly designed with the prospect of large numbers of defaults in mind — hence the engineering of subordinate tranches designed to protect the senior tranches from those defaults that occurred.

Completely incorrect. Several people who were very senior in these businesses told me that the worst case scenario we would ever see was, perhaps, home prices being flat for a few years. I never, not once, saw anyone run any scenarios with home price depreciation. Now, this being subprime, it was always assumed that individuals refinancing during the lowest interest rate period would start to default when both (a) rates were higher and (b) their interest rates reset. [Aside: Take note that this implicitly shows that people running these businesses knew that people were taking out loans they couldn’t afford.] Note that the creation of subordinate tranches, which were cut to exactly match certain ratings categories, was to (1) fuel the CDO market with product (obviously CDO’s were driven by the underlying’s ratings and were model based), (2) allow AAA buyers, including Fannie and Freddie, an excuse to buy bonds (safety!), and (3) maximize the economics of the execution/sale/securitization. If there were any reasons for tranches to be created, it had absolutely nothing to do with home prices or defaults.

Further, I would claim that there wasn’t even this level of detail applied to any analysis. We’ve seen the levels of model error that are introduced when one tries to be scientific about predictions. As I was told many times, “If we did business based on what the models tell us we’d do no business.” Being a quant, this always made me nervous. In retrospect, I’m glad my instincts were so attuned to reality.

As a matter of fact, most of the effort wasn’t on figuring out how to make money if things go bad or protect against downside risks, but rather most time and energy was spent reverse engineering other firm’s assumptions. Senior people would always say to me, “Look, we have to do trades to make money. We buy product and sell it off–there’s a market for securities and we buy loans based on those levels–at market levels.” These statements alone show how singularly minded these executives (I hate that term for senior people) and businesses were. The litmus test for doing risky deals wasn’t ever “Would we own these?” it was “Can we sell all the risk?”

But wait, there’s more…

Nor is it plausible that all concerned were simply mesmerized by, or cynically exploitive of, the willingness of rating agencies to stamp Triple-A on these securities. Wall Street firms knew what the underlying dog food consisted of, regardless of what rating was stamped on it. As noted, they willingly bet their firm’s money on it, and their own personal money on it, in addition to selling it to outsiders.

One needs the “willingly bet [their own] money on it” part to be true to make this argument. I know exactly what people would say, “We provide a service. We aggregate loans, create bonds, get those bonds rated, and sell them at the levels the market dictates. It isn’t our place to decide if our customers are making a good or bad investment decision.” I know it’s redundant with a lot of the points above, but that’s life–the underlying principles show up everywhere. And, honestly, it’s the perfect defense for, “How did you ever think this made sense?”

And, the last annoying bit I read and take issue with…

Nor is it true that Wall Street executives and CEOs had insufficient “skin in the game,” so that “perverse” compensation incentives created the mess. That story also does not pan out. Individuals, it’s true, were paid sizeable bonuses in the years in which the securities were created and sold.

[…]

Richard Fuld, of failed Lehman Brothers, saw his net worth reduced by at least a hundred million dollars. James Cayne of Bear Stearns was reported to have lost nearly a billion dollars in a matter of a few months. AIG’s Hank Greenberg, who remained a giant shareholder despite being removed from the firm he built by New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer in 2005, lost perhaps $2 billion. Thousands of lower-downs at these firms, those who worked in the mortgage securities departments and those who didn’t, also saw much wealth devastated by the subprime debacle and its aftermath.

Wow. Dick Fuld, who got $500 million, had his net worth reduced by $100 million? That’s your defense? And, to be honest, if you can’t gin up this discussion, then what can you gin up? The very nature of this debate is that all of these figures are unverifiable. James Cayne was reported to have lost nearly a billion dollars? Thanks, but what’s your evidence? The nature of rich people is that they hide their wealth, they diversify, and they skirt rules. So, sales of stock get fancy names like prepaid variable forwards. Show me their bank statements–even silly arguments need a tad of evidence, right?

Honestly, at this point I stopped reading. No point in going any further. So, now that you know how little regard for that which is already known and on the record this piece of fiction is, I’ll link to it…

Although, Felix does a great job of taking this piece down too (links above)… Although, he’s a bit less combative in his tone.

Nor is it plausible that all concerned were simply mesmerized by, or cynically exploitive of, the willingness of rating agencies to stamp Triple-A on these securities. Wall Street firms knew what the underlying dog food consisted of, regardless of what rating was stamped on it.