Today, in the Huffington Post, I posted a document that shows an earlier incarnation of the ABACUS trade (although, not that different from the one that has got the SEC up in arms). I also explained it as well as I could. Head on over and let me know what you think.

Archive for the ‘Risk’ category

Inside Goldman’s ABACUS Trade

April 19, 2010Charlie Gasparino Still Doesn’t Understand

January 5, 2010I recently wrote a piece about Goldman Sachs an took issue with some things Charlie Gasparino had said. He felt it was necessary, then, to write something about m article, but not really respond to it. It should come as no surprise that Mr. Gasparino’s response is as devoid of content as his original piece. I go through it here, line by line (my responses are in bold):

Why a Business Writer Wishes Wall Street Wasn’t Such a Big Story

Could it be because of the scrutiny that now is focused on the author of this missive?

I’ve been covering Wall Street now for nearly 20 years, and it’s been a pretty good run. I’ve broken some big stories and written three books about the “Street,” and I’m looking to write another. I’ve made some friends along the way — people like Teddy Forstmann, the great investor who called the junk-bond crisis and had the insight to steer clear of several others, and I’ve made some enemies, namely the traders and bankers who work at many of the big firms who would have preferred I kept silent about their problems during last year’s financial crisis rather than blab about them on CNBC.

I find this the source the mainstream media’s greatest power and the cause of their greatest weaknesses. Notice that Mr. Gasparino makes his success a function of how many stories he has broken. Did he get them right? Well, given his propensity to report gossip, merely skim the surface, and follow the meme of the day when giving his opinion, perhaps he’s just picking the most favorable metric.

The story about Wall Street is a big one — and I’m afraid to say, it’s going to get bigger in 2010 and beyond. If you want to know why the federal government allows all those community banks to fail, but bails out Citigroup, Bank of America, etc., with unlimited funding, it’s because these institutions have grown so large, and become so important and intertwined in the global financial system, that letting them fail would be catastrophic. In other words, it’s cheaper to guarantee Citigroup’s survival (and that of Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, JP Morgan) with hundreds of billions of dollars in bailout money as the government did last year, than watch the global banking system implode.

Honestly, I have no problem with this paragraph’s message. Too big to fail is a true problem and it evokes a lot of populist rage. I’m inclined to question his motives for putting this here, but I’m going to give him the benefit of the doubt (there’ll be plenty of opportunity to pick on actual errors, faulty logic, and cherry-picking later).

Now you may think I just can’t wait to cover this story in 2010. Of course, the journalist in me says, “bring it on”: another book and columns to write, big stories to cover. But the American citizen in me makes me wish Wall Street wasn’t such a big story, that people like Vikram Pandit of Citigroup and Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs (yes, the guy who thinks trading bonds is “God’s Work”) just weren’t such a big part of American life that the country’s economy rises and falls on their bad bets.

This last part makes no sense at all. So, American citizens merely want the media to stop covering Wall St. or cover it less? And it’s because Goldman and Citi are big parts of the “American life” that the economy rises and falls on their bad bets? In the interest of being charitable, I’ll just assume that he meant to say that he wishes that the events causing the story weren’t as severe as they have turned out to be and that the problems, not just the focus wasn’t all that big. You’re welcome Charlie.

I’ve come to this conclusion after reading two articles. One is a thoughtful but at bottom unrealistic piece written by several HuffPost contributors, including Arianna Huffington. It proposes that Americans remove their money from the large money-center banks at the center of the reckless risk taking that led to last year’s meltdown and bailouts, and move their deposits into community banks, the good guys of finance that didn’t take the risk because they weren’t Too Big To Fail.

Interesting that he likes this piece, but thinks it’s unrealistic. It’s like damning with faint praise. I also think he needed an article to say something positive about, so why not the one written (at least partially) by the person who distributes his writing to the masses?

The other is a less thoughtful post written by an anonymous blogger also on this site that defends Goldman Sachs and questions some of my reporting, including one piece from The Daily Beast that suggests Goldman’s all-too-obvious image problems have begun to impact its investment banking business.

Ahhhh… and here it is. My piece is being called less thoughtful by Charlie Gasparino? That’s like me calling a fish a bad swimmer. Further, he says that I defend Goldman Sachs. Can we all pause for a moment and reread the headling of the post, written by me, that he cites? It is, “2010 Will be Challenging for Goldman Sachs”–how he translates my thesis, that next year will be an uphill battle for Goldman, as defending Goldman is still totally unbelievable to me. As a matter of fact, it implies that he doesn’t understand the piece at all. Now that, I believe.

As for his questioning my conclusion that there is no evidence that Goldman’s investment banking business has been materially hurt by their image problems, well… I cite the league tables in the original article. Further, this shouldn’t even matter all that much since such a large percentage of Goldman’s profits come from their trading and principal investing (again, in the numbers, and the exact point of my article).

What I like about Arianna’s piece is that it attempts to hold the bad guys responsible. Its point is pretty simple: The likes of Citigroup and Bank of America don’t deserve our money, so let’s hit them hard and reward those who deserve our support, namely the community banks, who, despite many failures, didn’t engage in massive risk taking as the so-called large “money center” banks did over the past decade. The problem with the piece is twofold: First, community banks weren’t blameless in terms of risk taking and thus aiding and abetted the real estate bubble, which is the root cause of our economic problems. That’s why so many of them have failed and will continue to do so. Also, by making smaller community banks more important we might simply transfer the policy and status of Too Big To Fail to a different set of institutions. Armed with government support and subsidy from the Too Big To Fail precedent, what would stop community banks from taking excessive risk just as Citi has done?

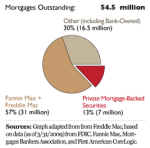

This paragraph is just silly. So, community banks are going to create hundreds of billions of dollars in CDOs? Could it be that smaller banks have failed because credit froze and they don’t have sophisticated hedging operations? Could it be that small banks have failed because they have loans as their primary assets and when the economy begins to have problems less people pay back their loans and banks take losses? Or, it could just be because they aided the real estate bubble. Although… Let’s take a look at this graphic from this ProPublica story (chopped a bit by me):

(Click for a larger version.)

Oh, right… If a small, community bank owns some mortgages, it means those mortgages weren’t securitized, and, thus, weren’t part of the massive overhang of toxic CDO assets that were made up of securitized mortgages. Finding this information cost me approximately five minutes on Google.

There are almost too many ways to attack the posting from the anonymous blogger (who goes by the name “Dear John Thain”), titled “2010 Will be A Challenging Year for Goldman Sachs,” (this guy obviously has a flair for understatement) so I will make the following points.

My comments will be more frequent now, as he’s getting to the good stuff. So far, all he says is (1.) the problems with my “posting” are numerous and (2.) I understated the problem in my title. He also promises to make multiple points…

Because he’s anonymous, we don’t know if he’s a Goldman executive (one way Goldman is now looking to attack its critics is by blogging positively about the firm, I am told) an investor with holdings of Goldman Sachs stock (a substantial conflict of interest if this is true), or just some guy with too much time on his hands.

This part is stupid, baseless, and implies Mr. Gasparino is backed into a corner. First, let me end this discussion now and forever by making the following statement: I am not now, nor have I ever been, an employee of Goldman Sachs or any of its subsidiaries. Further, I own no financial interest in Goldman or any of its subsidiaries. Second, I dare Mr. Gasparino to produce one shred of evidence, a comment on the record, or anything else indicating that Goldman is indeed using bloggers to defend them (Mr. Gasparino apaprently defines “blogging positively” as pointing out that Goldman almost certainly can’t reproduce its strong 2009 in 2010, as I did).

Beyond the mere infirm grasp of reality, this is where I think everyone who likes the blogosphere keeping the mainstream media honest, and indeed the blogosphere itself, should be deeply offended by what Mr. Gasparino has done. Mr. Gasparino has resorted to a sort of McCarthyism where insinuating someone who doesn’t wish to divulge their own identity is planted her by Goldman–a firm better known for suing bloggers than spawning them. This is insulting and should not be tolerated by any thinking person. The people who know the most about finance are the people who work in it. I make zero dollars from my blog and my writing. So many others risk their futures and livelihoods by writing, only to explain what is actually going on to those that are interested.

In fact, Charlie Gasparino, and his ilk, are the reason we exist. If he didn’t have the accuracy of a backfiring gun when it comes to issues other than gossip we, the pseudonymed finance writers, wouldn’t be needed. The public would understand financial topics much better and the record wouldn’t need to be set straight by those in the know. And now, when faced with someone correcting him on the record, he merely wishes to dismiss the facts and figures put before him and insinuate something for which he has no facts. Honestly, this speaks volumes about his regard for the truth and his ability to justify his own words when challenged.

This sort of attack should be rebuked as swiftly and sternly as it was introduced.

In any event, one line caught my eye: He takes issue with my assertion that Goldman benefits from a subsidy from the government because of its status now as a bank; he says it’s really a “financial holding company” as opposed to a “bank holding company” but fails to point out that there’s really no difference.

Honestly, Mr. Gasparino should either stop saying patently false things and merely learn to read. There is a major difference. Banks have stringent capital requirements. Financial holding companies do not. Let me pose a simple question, keeping in mind the distinction I just made. Is a financial holding company that owns a bank and a broker-dealer (the broker-dealer having a $1 trillion balance sheet) the same as being a bank with a $1 trillion balance sheet? Absolutely not. Banks cannot own certain sorts of assets, don’t have trading portfolios that need to marked to market every day, and are severely limited in terms of how much leverage they can take on. A broker-dealer, however, can take much riskier positions, can be more leveraged, and have different accounting rules (in addition to costs of funding). Mr. Gasparino did get one thing right, I failed to point out something that was patently false.

In the aftermath of the financial meltdown and bailout, Goldman is now primarily regulated by the Fed (as opposed to the Securities and Exchange Commission), the banking system’s chief regulator, and receives along with that all the benefits of the classification, including being treated in the market as Too Big To Fail, and thus being able to borrow cheaply.

Goldman the “financial holding company” is regulated by the Fed. Goldman’s bank is regulated by bank regulators. Goldman’s securities businesses are regulated by securities regulators. This is why people working inside large “financial supermarket” institutions have heard the expression “bank chain vehicle” and similar terms, the regulator for a specific division matters.

Here’s another fun fact that shows Mr. Gasparino has no idea what is saying: Goldman Sachs has had cheaper costs of borrowing (as shown by their credit default swaps) than Citi, the ultimate example of being way too big to exist.

As I pointed out in my book The Sellout, there’s much to admire about Goldman and its history in risk taking compared with the other big firms; this was, of course, the only firm to question its own irrational exuberance and short the subprime real estate market back in late 2006 (a trade in which a firm makes money if prices decline) whiles it competitors were betting bigger on the bubble. But that hedge only delayed the inevitable — Goldman, like the rest of the financial business (except maybe JP Morgan), bet big and wrong, so wrong that by the fall of 2009 it, along with most of its competitors, was falling into insolvency.

Fall of 2009? So, I guess the billions in profit Goldman reported for the third quarter of 2009 was all smoke and mirrors. Maybe he means 2008? Or maybe he’s more confused about what he wrote than I am.

All of which brings me to the bigger point of this piece: We as journalists, as commentators, and policy makers spend way too much time arguing over the fine points of Goldman’s status as a bank holding company or a financial holding company. Lloyd Blankfein is pilloried for saying he does God’s Work when he trades stocks or bonds, when in a more perfect world, what he says or what he does just shouldn’t mean that much to the guy who owns an auto repair shop in Queens or the family farmer in Iowa.

Charlie Gasparino, lumping himself in with policy makers, is being charitable. I want the people who make the law to argue over whether or not certain institutions should be allowed to employ certain types of corporate structures. I want the actual facts to be part of the public discourse and guide policy. Given the errors Mr. Gasparino tends to make, I can see why arguing over the specifics wouldn’t hold much appeal.

That’s why I kind of like Arianna’s idea (despite its drawbacks) of empowering community banks as opposed to the money center banks that are way too important and powerful and whose leaders just shouldn’t wield that type of influence because at bottom they’re just not smart enough — nor, perhaps, is anyone. Dear John Thain’s nom de plume is a reference, of course, to the former CEO of Merrill Lynch John Thain, who by all accounts didn’t think twice about spending more than $1 million decorating his office during the financial crisis, including tens of thousands on a high-end commode.

Make no mistake, the reference to John Thain “tricking out” his office has no place in the discussion. If Mr. Gasparino can’t take the time to read my About page, then at least he did as much research on me as he did for his actual articles.

To be sure, bankers have always wielded enormous power in our society — JP Morgan was a real person, after all. But somehow the importance of people like John Thain (whose spending spree also included a $1,400 parchment paper waste basket) and Lloyd Blankfein has grown beyond anyone’s comprehension, even their own. When former Lehman Brothers CEO Dick Fuld was rebuffing offers to buy his firm before its free fall into bankruptcy last year, I don’t think he truly envisioned the power of his inaction: That the entire financial system would shut down as a consequence of holding out for more money. One of the great lessons of the financial crisis is that this power was bestowed on the wrong people — the people who helped foment the housing bubble (along with the government) by packaging all those risky mortgages into allegedly safe bonds and then took so much risk that they destroyed the financial system and created the Great Recession and with it 10 percent unemployment.

Amazing. Once again he references John Thain’s excessive decorating budget. This is about as useful as me accusing Mr. Gasparino of being a murderer because his first name is the same as Charlie Manson. The other points in the paragraph are actually true: financial C.E.O.’s have a lot of power and have a huge impact on our financial system. This is why their industry is heavily regulated. The ending of his rant, about “the wrong people” and all that, is nonsense and vague. I’d dissect it further, but I’m tired.

It would be nice if in the not so distant future the Dick Fulds and Lloyd Blankfeins of the world become less important, even if I lose a book deal in the process.

I, too, think it would be nice if Mr. Gasparino had less of an opportunity to be in the public eye. But then again, I bet you already knew that.

Why 2010 will be Challenging for Goldman Sachs

December 30, 2009I figured I’d let 2009 go out with a bang and post another of my contrarian views: 2010 will be rough for Goldman Sachs. Why? Well, to know the answer to that, you should head on over to the Huffington Post where the full piece is online.

Happy New Year!

A Recounting of Recent History

July 28, 2009Yes, I’m alive! I’m terribly sorry for the extended silence, but I’ve had some big changes going on in my personal life and have been out of the loop for a while (honestly, my feed reader needs to start reading itself–I have over 1,000 unread posts when looking at just 4 financial feeds). So, here’s what I haven’t had a chance to post…

1. I totally missed the most recent trainwreck of a P.R. move at Citi. There is so much crap going on around Citi… I really intend to write a post that is essentially a linkfest of Citi material that stitches together the narrative of how Citi got into this mess and how Citi continues to do itself no favors. There was also a completely vapid opinion piece from Charlie Gasperino that said absolutely nothing new, save for one sentence, and then ended with a ridiculous comparison that was clearly meant to generate links. I’m not even going to link to it… It was on the Daily Beast, if you must find it.

2. I haven’t really had the opportunity to comment on the Obama administration’s overhaul of the financial regulatory apparatus. Honestly, it sucks. It doesn’t do much and gives too much power to the Fed. You’d think that after that recent scandal within the ranks of the Fed there would be a political issue with giving it more power. Even more interestingly, all other major initiatives from the Obama administration have been drafted by congress. Here, the white paper came from the Whitehouse itself. That won’t do too much to quiet the critics who are claiming that the Whitehouse is too close to Wall St. Honestly, if one is to use actions instead of words to measure one’s intentions, then it’s hard to point to any evidence that the Obama administration isn’t in the bag for the financial services industry.

3. The Obama administration did an admirable job with G.M. and Chrysler. They were both pulled through bankruptcy, courts affirmed the actions, and there was a minimal disruption in their businesses. Stakeholders were brought to the table, people standing to lose from the bankruptcy, the same people (I use that word loosely–most are institutions) who provided capital to risky enterprises, were forced to take losses, and the U.S.A. now has something it has never had: an auto industry where the U.A.W. has a stake and active interest in the companies that employ its members. Perhaps the lesson, specifically that poorly run firms that need to be saved should cause consequences for the people who caused the problems (both by providing capital and providing inadequate management), will take hold in the financial services sector too–I’m not holding my breath, though.

4. Remember this problem I wrote about? Of course not, that is one of my least popular posts! However, some of the questions are being answered. Specifically, the questions about how and when the government will get rid of its ownership stakes, and at what price, are starting to be filled in. It was rather minor news when firms started paying T.A.R.P. funds back. However, the issue of dealing with warrants the government owns was a thornier issue. Two banks have dealt with this issue–Goldman purchased the securities at a price that gives the taxpayers a 23% return on their investment and JP Morgan decided that it would forgo a negotiated purchase and forced the U.S. Treasury to auction the warrants.

On a side note: From this WSJ article linked to above, its a bit maddening to read this:

The Treasury has rejected the vast majority of valuation proposals from banks, saying the firms are undervaluing what the warrants are worth, these people said. That has prompted complaints from some top executives. […] James Dimon raised the issue directly with Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, disagreeing with some of the valuation methods that the government was using to value the warrants.

(Emphasis mine.)

If I were on the other end of the line, my response would be simple: “Well, Jamie, I agree. The assumptions we use to value securities here at the U.S. government can be, well … off. So, we’ll offer you what you think is fair for the warrants if you’ll pay back the $4.4 billion subsidy we paid when we initially infused your bank with T.A.R.P. funds.” Actually, I probably would have had a meeting with all recipients about it and quoted a very high price for these warrants and declared the terms and prices non-negotiable–does anyone really think that, in the face of executive pay restrictions, these firms wouldn’t have paid whatever it would take to get out from under the governments thumb? As long as one investment banker could come up with assumptions that got the number, they would have paid it. Okay, that’s all for my aside.

5. I’m dreadfully behind on my reading… Seriously. Here’s a list of articles I haven’t yet read, but intend to…

- The Science of Economic Bubbles and Busts — A scientific look at bubbles, specifically the psychology.

- Sheila Bair, FDIC, and the financial crisis — A profile of Sheila Bair. I find the New Yorker profiles very good and nearly impossibly long.

- Rich Harvard, Poor Harvard: Vanity Fair — An interesting look at Harvard and how its fortunes interplay with its endowment and its in-house money manager.

- Prophet Motive — A profile of Nouriel Roubini. My gut tells me he’s a case study in being more lucky than right, but I haven’t read it, so who knows.

- The Way We Live Now – Diminished Returns — A NY Times article whose title makes too much sense to pass up!

- Confessions of a Bailout CEO Wife — As close as I’ll ever get to US Weekly.

- What Does Your Credit-Card Company Know About You? — Ugh. My gut tells me too much. As a Consumerist reader, I think I know what this is, but we’ll see.

- At Geithner’s Treasury, Key Decisions on Hold — An article that got a lot of play as a good case study.

- Paulson’s Complaint — Paulson claiming Lehman didn’t cause the huge problems in the markets and economy that followed its bankruptcy. I don’t buy it.

- The Crisis and How to Deal with It — A weird multi-person article in the New York Review of Books.

- The New York Fed is the most powerful financial institution you’ve never heard of. Look who’s running it — A Slate article by Eliot Spitzer. I admit to not really get the Fed system.

- Tracking Loans Through a Firm That Holds Millions — A look at a servicer, I believe.

- Flawed Credit Ratings Reap Profits as Regulators Fail — Wow. Based on the title, I must have dangerously low blood pressure that needs boosting!

- The formula that felled Wall St — Another look at Gaussian Copula, I think. Felix, also looked at this.

- Peter Orszag and the Obama budget — Another New Yorker profile.

- Geithner, Member and Overseer of Finance Club — A NY Times profile of Tim.

- HMC Tax Concerns Aided Federal Inquiries — Interestingly, an article that got national press, is an investigative piece, and deals with finance from a college newspaper!

- Treasury Chief Tim Geithner Profile –Portfolio profile of Tim. I’ll know everything about him by the end of this list.

- Lewis Testifies U.S. Urged Silence on Deal — I really don’t know about this situation. I want to read up and understand all the details.

- The Wail of the 1% — Honestly, not sure. Talking about the plight of the rich?

- Economic View – Why Creditors Should Suffer, Too — The title makes me want to read this. Confirmation bias, perhaps?

- How Bernanke Staged a Revolution — A profile of Ben Bernanke by the WaPo.

- 5 Ways Companies Breed Incompetence — Just five?

- Ten principles for a Black Swan-proof world — An opinion piece from the FT by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

- A New Era for Financial Regulation — Megan McArdle looks at the proposed regulatory structure. Honestly, I don’t read her, so I’m skeptical about this piece.

- U.S. Plan to Stem Foreclosures Is Mired in Paper Avalanche — Not sure. One of the longer NY Times pieces.

- Bill Gross of Pimco Is on Treasury’s Speed Dial — A profile of Pimco’s role in fixing the financial problems, conflicts, etc.

- Congress Helped Banks Defang Key Rule — Another fix for low blood pressure.

- Timothy Geithner and Lawrence Summers – The Case for Financial Regulatory Reform — OpEd by Geithner and Summers.

- SEC Chief Strives To Rebuild Regulator — An article on the problems at the S.E.C.

- A Daring Trade Has Wall Street Seething — A writeup of how a small firm worked the system to make money. Should be interesting.

- President’s Economic Circle Keeps Tensions at a Simmer — An interesting case study on how Obama’s economic team works.

- Back to Business – Banks Dig In to Resist New Limits on Derivatives — Hey! We’re paying banks to spend money to lobby ourselves to not regulate them so they can profit off of our money! Sweet!

I hope to get more time to post in the coming days. Also, I am toying with the idea of writing more frequent, much shorter posts. On the order of a paragraph where I just toss out a thought. Not really my style, but maybe it would be good. Feedback appreciated.

Revisiting a Debate We Should be Past

June 10, 2009Recently, Felix Salmon, Clusterstock, and others have been mentioning an essay from the Hoover Institute about the financial crisis. Now, I haven’t yet linked to the essay in question… I will, but only after I’ve said some thing about it.

I was on the front lines of the securitization boom. I saw everything that happened and am intimately familiar with how one particular bank, and more generally familiar with many banks’, approach to these businesses. I think that there are no words that adequately describes how utterly stupid it is that there is still a “debate” going on surrounding banks and their roles in the financial crisis. There are no unknowns. People have been blogging, writing, and talking about what happened ad naseum. It’s part of the public record. Whomever the author of this essay is (I’m sure I’ll be berated for not knowing him like I was for not knowing Santelli — a complete idiot who has no place in a public conversation whose requisites are either truth or the least amount of intellectual heft), unless it’s writing was an excesses in theoretical reasoning about a parallel universe, it’s a sure sign they don’t what they are talking about that they make some of the points in the essay. Let’s start taking it apart so we can all get on with our day.

For instance, it isn’t true that Wall Street made these mortgage securities just to dump them on them the proverbial greater fool, or that the disaster was wrought by Wall Street firms irresponsibly selling investment products they knew or should have known were destined to blow up. On the contrary, Merrill Lynch retained a great portion of the subprime mortgage securities for its own portfolio (it ended up selling some to a hedge fund for 22 cents on the dollar). Citigroup retained vast holdings in its so-called structured investment vehicles. Holdings of these securities, in funds in which their own employees personally participated, brought down Bear Stearns and Lehman Brothers. AIG, once one of the world’s most admired corporations, made perhaps the biggest bet of all, writing insurance contracts against the potential default of these products.

So Wall Street can hardly be accused of failing to eat its own dog food. It did not peddle to others an investment product that it was unwilling to consume in vast quantities itself.

(Emphasis mine.)

Initial premise fail. I had a hard time finding the part to emphasize since it’s all so utterly and completely wrong. Since I saw everything firsthand, let me be unequivocal about my remarks: the entire point of the securitization business was to sell risk. I challenge anyone to find an employee of a bank who says otherwise. This claim, that “it isn’t true that Wall Street made these mortgage securities just to dump them on them the proverbial greater fool” is proven totally false. There’s a reason the biggest losers in this past downturn were the biggest winners in the “league tables” for years running. As a matter of fact, there’s a reason that league tables, and not some other measure, were a yardstick for success in the first place! League tables track transaction volume–do I really need to point out that one doesn’t judge themselves by transaction volume when their goal isn’t to merely sell/transact?

In fact, the magnitude of writedowns by the very firms mentioned (Merrill and Citi) relative to the original value of these investments imply that a vast, vast majority of the holdings were or were derived from the more shoddily underwritten mortgages underwritten in late 2006, 2007, and early 2008. In fact, looking at ABX trading levels, as of yesterday’s closing, shows the relative quality of these mortgages and makes my point. AAA’s from 2007 (series 1 and 2) trading for 25-26 cents on the dollar and AAA’s from early 2006 trading at roughly 67 cents on the dollar. The relative levels are what’s important. Why would Merrill be selling it’s product for 22 cents on the dollar if the market level is so much higher (obviously the sale occurred a few months ago, but the “zip code” is still the same)? This is a great piece of evidence that banks are merely left holding the crap they couldn’t sell when the music stopped.

Now, onto the next stop on the “How wrong can you get it?” tour.

It isn’t true, either, that Wall Street manufactured these securities as a purblind bet that home prices only go up. The securitizations had been explicitly designed with the prospect of large numbers of defaults in mind — hence the engineering of subordinate tranches designed to protect the senior tranches from those defaults that occurred.

Completely incorrect. Several people who were very senior in these businesses told me that the worst case scenario we would ever see was, perhaps, home prices being flat for a few years. I never, not once, saw anyone run any scenarios with home price depreciation. Now, this being subprime, it was always assumed that individuals refinancing during the lowest interest rate period would start to default when both (a) rates were higher and (b) their interest rates reset. [Aside: Take note that this implicitly shows that people running these businesses knew that people were taking out loans they couldn’t afford.] Note that the creation of subordinate tranches, which were cut to exactly match certain ratings categories, was to (1) fuel the CDO market with product (obviously CDO’s were driven by the underlying’s ratings and were model based), (2) allow AAA buyers, including Fannie and Freddie, an excuse to buy bonds (safety!), and (3) maximize the economics of the execution/sale/securitization. If there were any reasons for tranches to be created, it had absolutely nothing to do with home prices or defaults.

Further, I would claim that there wasn’t even this level of detail applied to any analysis. We’ve seen the levels of model error that are introduced when one tries to be scientific about predictions. As I was told many times, “If we did business based on what the models tell us we’d do no business.” Being a quant, this always made me nervous. In retrospect, I’m glad my instincts were so attuned to reality.

As a matter of fact, most of the effort wasn’t on figuring out how to make money if things go bad or protect against downside risks, but rather most time and energy was spent reverse engineering other firm’s assumptions. Senior people would always say to me, “Look, we have to do trades to make money. We buy product and sell it off–there’s a market for securities and we buy loans based on those levels–at market levels.” These statements alone show how singularly minded these executives (I hate that term for senior people) and businesses were. The litmus test for doing risky deals wasn’t ever “Would we own these?” it was “Can we sell all the risk?”

But wait, there’s more…

Nor is it plausible that all concerned were simply mesmerized by, or cynically exploitive of, the willingness of rating agencies to stamp Triple-A on these securities. Wall Street firms knew what the underlying dog food consisted of, regardless of what rating was stamped on it. As noted, they willingly bet their firm’s money on it, and their own personal money on it, in addition to selling it to outsiders.

One needs the “willingly bet [their own] money on it” part to be true to make this argument. I know exactly what people would say, “We provide a service. We aggregate loans, create bonds, get those bonds rated, and sell them at the levels the market dictates. It isn’t our place to decide if our customers are making a good or bad investment decision.” I know it’s redundant with a lot of the points above, but that’s life–the underlying principles show up everywhere. And, honestly, it’s the perfect defense for, “How did you ever think this made sense?”

And, the last annoying bit I read and take issue with…

Nor is it true that Wall Street executives and CEOs had insufficient “skin in the game,” so that “perverse” compensation incentives created the mess. That story also does not pan out. Individuals, it’s true, were paid sizeable bonuses in the years in which the securities were created and sold.

[…]

Richard Fuld, of failed Lehman Brothers, saw his net worth reduced by at least a hundred million dollars. James Cayne of Bear Stearns was reported to have lost nearly a billion dollars in a matter of a few months. AIG’s Hank Greenberg, who remained a giant shareholder despite being removed from the firm he built by New York Attorney General Eliot Spitzer in 2005, lost perhaps $2 billion. Thousands of lower-downs at these firms, those who worked in the mortgage securities departments and those who didn’t, also saw much wealth devastated by the subprime debacle and its aftermath.

Wow. Dick Fuld, who got $500 million, had his net worth reduced by $100 million? That’s your defense? And, to be honest, if you can’t gin up this discussion, then what can you gin up? The very nature of this debate is that all of these figures are unverifiable. James Cayne was reported to have lost nearly a billion dollars? Thanks, but what’s your evidence? The nature of rich people is that they hide their wealth, they diversify, and they skirt rules. So, sales of stock get fancy names like prepaid variable forwards. Show me their bank statements–even silly arguments need a tad of evidence, right?

Honestly, at this point I stopped reading. No point in going any further. So, now that you know how little regard for that which is already known and on the record this piece of fiction is, I’ll link to it…

Although, Felix does a great job of taking this piece down too (links above)… Although, he’s a bit less combative in his tone.

Nor is it plausible that all concerned were simply mesmerized by, or cynically exploitive of, the willingness of rating agencies to stamp Triple-A on these securities. Wall Street firms knew what the underlying dog food consisted of, regardless of what rating was stamped on it.

Mild Skepticism: Credit Card Bill of Rights Edition

May 21, 2009Well, we can all rest assured that H.R. 627, the Credit Cardholders’ Bill of Rights Act of 2009, will indeed pass. I’ve been a huge advocate of strengthening consumer protection in the past, so this is a welcomed change. However, I’m worried that legislators have managed to put restrictions and requirements on credit card companies without taking the last step: making them ineligible to be waived in boiler-plate language. Or, more importantly, the difference between “opt out” and “opt in” … From the text of the bill:

‘(k) Opt-in Required for Over-the-Limit Transactions if Fees Are Imposed-

‘(1) IN GENERAL- In the case of any credit card account under an open end consumer credit plan under which an over-the-limit fee may be imposed by the creditor for any extension of credit in excess of the amount of credit authorized to be extended under such account, no such fee shall be charged, unless the consumer has expressly elected to permit the creditor, with respect to such account, to complete transactions involving the extension of credit under such account in excess of the amount of credit authorized.

‘(2) DISCLOSURE BY CREDITOR- No election by a consumer under paragraph (1) shall take effect unless the consumer, before making such election, received a notice from the creditor of any over-the-limit fee in the form and manner, and at the time, determined by the Board. If the consumer makes the election referred to in paragraph (1), the creditor shall provide notice to the consumer of the right to revoke the election, in the form prescribed by the Board, in any periodic statement that includes notice of the imposition of an over-the-limit fee during the period covered by the statement.

‘(3) FORM OF ELECTION- A consumer may make or revoke the election referred to in paragraph (1) orally, electronically, or in writing, pursuant to regulations prescribed by the Board. The Board shall prescribe regulations to ensure that the same options are available for both making and revoking such election.

‘(4) TIME OF ELECTION- A consumer may make the election referred to in paragraph (1) at any time, and such election shall be effective until the election is revoked in the manner prescribed under paragraph (3).

(Emphasis mine.)

Now, you’ll notice that any election remains in force until one revokes it. Also, you’ll notice that there are periodic disclosure requirements. For educated consumers (for example, readers of The Consumerist or the Wall St. Journal’s personal finance blog “The Wallet”) this should sound familiar. It’s well established that credit cards already contain language describing how they treat information they collect on you–most sell or share this information. As this FDIC page says, though, you can usually opt out. Raise your hand if you’ve ever, in all your time on this round ball of dirt, seen how to opt out or been told of this ability by anyone (other than me, just now). If more than 0.5% of you are raising your hand, there are liars galore reading. Now, opting out on those particular issue is a different animal–there are lots of forms of information sharing you cannot opt out of. In fact, credit bureaus can sell your information too. (Wouldn’t it be nice if this legislation fixed these practices as well?) Despite these differences, the point remains that opt in protections can be abused and aren’t really protections at all. As a matter of fact, it would be nice if we saw protections that were non–waive-able.

Just goes to show that, even when considering laws strengthening consumers’ protection against abusive practices, it pays to read the fine print.

Notes and Predictions: The Stress Test

May 6, 2009As the results of the stress test start leaking out slowly, it’s a fun exercise to make some educated guesses/predictions about what the future holds and take note of pertinent facts. As we’ve discussed before, there is a lot to take issue with when considering the results of the stress test at all, especially given the added layers of uncertainty stemming form the limited information provided in the scenarios. So, without further delay, let’s get started.

1. The baseline scenario will prove wholly inadequate as a “stress test.” Please, follow along with me as I read from the methodology (pdf). I’ll start with the most egregious and reckless component of the mis-named baseline scenario (I would rename it the, “if payer works” scenario) : what I will refer to as “the dreaded footnote six.” From the document:

As noted above, BHCs [(Bank Holding Companies, or the firms being stress tested)] with trading account assets exceeding $100 billion as of December 31, 2008 were asked to provide projections of trading related losses for the more adverse scenario, including losses from counterparty credit risk exposures, including potential counterparty defaults, and credit valuation adjustments taken against exposures to counterparties whose probability of default would be expected to increase in the adverse scenario.(6)

[…]

(6) Under the baseline scenario, BHCs were instructed to assume no further losses beyond current marks.

(Emphasis mine.)

Holy <expletive>! In what alternate/parallel/baby/branching universe is this indicative of anything at all? Assume no further losses beyond current marks? Why not assume everything returns to par? Oh, well, that actually was a pretty valid assumption for the baseline scenario. From the document:

New FASB guidance on fair value measurements and impairments was issued on April 9, 2009, after the commencement of the [stress test]. For the baseline scenario supervisors considered firms’ resubmissions that incorporated the new guidance.

(Emphasis mine.)

Thank goodness! I was worried that the “if prayer works” scenario might have some parts that were worth looking at. Thankfully, for troubled banks, I can skip this entire section. (Confidence: 99.9999%)

2. Trading losses will be significantly understated across all five institutions that will need to report them. First, only institutions with over $100 billion in trading assets were asked to stress their trading positions. Second, from the section on “Trading Portfolio Losses” from the document:

Losses in the trading portfolio were evaluated by applying market stress factors … based on the actual market movements that occurred over the stress horizon (June 30 to December 31, 2008).

(Emphasis mine.)

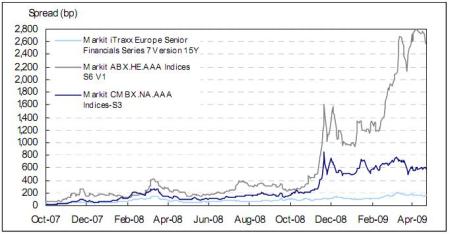

Okay, well, that seems reasonable, right? Hmmmm… Let’s take a look. Here is what some indicative spread movements for fixed income products looked like January 9th of 2009, according to Markit (who has made it nearly impossible to find historical data for their indices, so I’m resorting to cutting and pasting images directly–all images are from their site):

(Click on the picture for a larger version.)

Well, looks like a big move is taken into account by using this time horizon. Clearly this should provide a reasonable benchmark for the stress test results, right? Well, maybe not.

(Click on the picture for a larger version.)

Yes, that’s right, we’ve undergone, for sub-prime securities a massive widening during 2009 already. Also, as far as I can tell, the tests are being run starting from the December 2008 balance sheet for each company. So, if I’m correct, for the harsher scenario, trading losses will be taken on December 2008 trading positions using December 2008 prices and applying June 2008 to December 2008 market movements. For sub-prime, it seems pretty clear that most securities would be written up (June 2008 Spread: ~200, December 2008 Spread: ~1000, Delta: ~800, Current Spread: ~2600, December 2008 to Today Delta: ~1600, Result: firms would take, from December 2008 levels, half the markdown they have already taken).

Also, it should be a shock to absolutely no one that most trading assets will undergo a lagged version of this same decline. Commercial mortgages and corporate securities rely on how firms actually perform. Consumer-facing firms, as unemployment rises, the economy worsens and consumption declines, and consumers default, will see a lagged deterioration that will appear in corporate defaults and small businesses shuttering–both of these will lead to commercial mortgages souring. Indeed we’ve seen Moody’s benchmark report on commercial real estate register a massive deterioration in fundamentals. That doesn’t even take into account large, exogenous events in the sector. Likewise, we see consistently dire predictions in corporate credit research reports that only point to rising defaults 2009 and 2010.

In short, for all securities, it seems clear that using data from 2H2008 and applying those movements to December 2008 balance sheets should produce conservative, if not ridiculously understated loss assumptions. (Confidence: 90%)

3. Bank of America will have to go back to the government. This, likely, will be the end of Ken Lewis. It’s not at all clear that Bank of America even understands what’s going on. First, if I’m correctly reading Bank of America’s first quarter earnings information, the firm has around $69 billion in tangible common equity. Also, it should be noted that the FT is reporting that Bank of America has to raise nearly $34 billion. Now, with all this in mind, let’s trace some totally nonsensical statements that, unlike any other examples in recent memory, were not attributed to anonymous sources (from the NYT article cited above):

The government has told Bank of America it needs $33.9 billion in capital to withstand any worsening of the economic downturn, according to an executive at the bank. […]

But J. Steele Alphin, the bank’s chief administrative officer, said Bank of America would have plenty of options to raise the capital on its own before it would have to convert any of the taxpayer money into common stock. […]

“We’re not happy about it because it’s still a big number,” Mr. Alphin said. “We think it should be a bit less at the end of the day.” […]

Regulators have told the banks that the common shares would bolster their “tangible common equity,” a measure of capital that places greater emphasis on the resources that a bank has at its disposal than the more traditional measure of “Tier 1” capital. […]

Mr. Alphin noted that the $34 billion figure is well below the $45 billion in capital that the government has already allocated to the bank, although he said the bank has plenty of options to raise the capital on its own.

“There are several ways to deal with this,” Mr. Alphin said. “The company is very healthy.”

Bank executives estimate that the company will generate $30 billion a year in income, once a normal environment returns. […]

Mr. Alphin said since the government figure is less than the $45 billion provided to Bank of America, the bank will now start looking at ways of repaying the $11 billion difference over time to the government.

(Emphasis mine.)

Right around the time you read the first bolded statement, you should have started to become dizzy and pass out. When you came to, you saw that the chief administrative officer, who I doubt was supposed to speak on this matter (especially in advance of the actual results), saying that a bank with $69 billion in capital would be refunding $11 billion of the $45 billion in capital it has already received because they only need $34 billion in capital total. Huh? Nevermind that the Times should have caught this odd discrepancy, but if this is the P.R. face the bank wants to put on, they are screwed.

Now, trying to deal with what little substance there is in the article, along with the FT piece, it seems pretty clear that, if Bank of America needs $34 billion in additional capital, there is no way to get it without converting preferred shares to common shares. There is mention of raising $8 billion from a sale of a stake in the China Construction Bank (why are they selling things if they are net positive $11 billion, I don’t know). That leaves $26 billion. Well, I’m glad that “once a normal environment returns” Bank of America can generate $30 billion in income (Does all of that fall to T.C.E.? I doubt it, but I have no idea). However, over the past four quarters, Bank of America has added just $17 billion in capital… I will remind everyone that this timeframe spans both T.A.R.P. and an additional $45 billion in capital being injected into the flailing bank. Also, who is going to buy into a Bank of America equity offering now? Especially $26 billion of equity! If a troubled bank can raise this amount of equity in the current environment, then the credit crisis is over! Rejoice!

I just don’t see how Bank of America can fill this hole and not get the government to “bail it out” with a conversion. The fact that Bank of America argued the results of the test, frankly, bolsters this point of view. Further, this has been talked about as an event that requires a management change, hence my comment on Lewis. (Confidence: 80% that the government has to convert to get Bank of America to “well capitalized” status)

Notes/Odds and Ends:

1. I have no idea what happened with the NY Times story about the results of the “Stress Test.” The WSJ and FT are on the same page, but there could be something subtle that I’m misunderstanding or not picking up correctly. Absent this, my comments stand. (Also, if might have been mean.unfair of me to pick on the content of that article.)

2. The next phases of the credit crisis are likely to stress bank balance sheets a lot more. The average bank doesn’t have huge trading books. However, they do have consumer-facing loan and credit products in addition to corporate loans and real estate exposure. In the coming months, we’ll see an increase in credit card delinquencies. Following that, we’ll see more consumer defaults and corporations’ bottom line being hurt from the declining fundamentals of the consumer balance sheet. This will cause corporate defaults. Corporate defaults and consumer defaults will cause commercial real estate to decline as well. The chain of events is just beginning. Which leads me to…

3. Banks will be stuck, unable to lend, for a long time. I owe John Hempton for this insight. In short, originations require capital. Capital, as we see, is in short supply and needed to cover losses for the foreseeable future. Hence, with a huge pipeline of losses developing and banks already in need of capital, there is likely not going to be any other lending going on for a while. This means banks’ ability to generate more revenue/earnings is going to be severely handicapped as sour loans make up a larger and larger percentage of their portfolios.

4. From what I’ve read, it seems that the actual Citi number, for capital to be raised, is between $6 billion and $10 billion. This puts their capital needs at $15 billion to $19 billion, since they are selling assets to raise around $9 billion, which is counted when considering the amount of capital that needs to be raised (according to various news stories). Interestingly, this is 44% to 55% of Bank of America’s needed capital. This paints a very different picture of the relative health of these two firms than the “common wisdom” does. Granted, this includes a partial conversion of Citi’s preferred equity to common equity.

5. I see a huge correlation between under-performing portfolios and a bank trying to negotiate it’s required capital lower by “appealing” the stress test’s assessment of likely losses in both the baseline and adverse scenarios. As I’ve talked about before, not all portfolio performance is created equal. Citi has seen an increasing (and accelerating) trend in delinquencies while JP Morgan has seen it’s portfolio stabilize. So, for the less-healthy banks to argue their losses are overstated by regulators, they are doubly wrong. It’ll be interesting to see how this plays out–for example, if JP Morgan’s credit card portfolio assumes better or worse performance than Citi and Bank of America.

Guest Post at Clusterstock

April 23, 2009Hey, I wanted to let you, my loyal readers, know that I guest posted over at Clusterstock. The post, entitled “Investment Bank Scorecard” is my take on this past quarter as a whole. I think it’s worth clicking over and taking a look. I’d sum it up here, but, in all honesty, the value is in the nuances and small insights more than the general thesis.

Also, here is the chart attached to that post, in its orginal form.

Repaying T.A.R.P.: There Are Restrictions

April 21, 2009There is a meme (did you know that word was invented by Richard Dawkins?) going around the blogosphere that, in essence, says Geithner doesn’t have the right to prevent T.A.R.P. repayment, even if no fresh capital is raised. This is incorrect. From the Goldman Sachs T.A.R.P. agreements [pdf!] governing the capital infusion (it’s hidden on the site, but there!):

(Emphasis [yes, that’s the green underlining] mine.)

Seems, then, that it’s pretty clear. Whole or partial payments, once allowed by a regulator, require fresh equity raised from a “Qualified Equity Offering.” This is a defined term, and the document defines it as follows:

So, it seems pretty cleat that there are conditions. Now, maybe these aren’t the systemic considerations, but that’s likely why the regulatory approval is required, especially in conjunction with the “stress test,” which we’ve discussed here at length.

How to Fix the Compensation Issue… Yesterday!

April 15, 2009With all the tone-deafness that followed the great compensation debate of 2009, I have a very simple solution. The problem, despite what people commonly believe, is not the absolute level of compensation. No, it’s the fact that management’s personal incentives and employees’ incentives are aligned–shareholders are still in the wilderness. How many times have we heard the trite, absolutely silly refrain stating “we need to pay the valuable people that know where the bodies are buried so they can dispose of them!”? Way too many. Although, there are dozens of examples of retention bonuses being paid to people as they resign… Idiots.

So, what do I suggest? Add all compensation, beyond a base limit, say $250,000, as T.A.R.P. debt to institutions who have already received funds under the program–and the interest rate from this new debt should be very high. I would suggest… okay, I never merely suggest… I would demand (better!) that this new debt carry a high coupon. Maybe even ensure the interest owed is cutely linked to the way these publicly owned (partially, anyway) institutions are negatively impacting our economy. One example: this new debt could carry an interest rate equal to the greater of the (a) median of the top quartile of credit card interest rates issued by the company in question and (b) 24.99%.

Now, what does this do? It better aligns management and shareholders. How can a C.E.O. allow divisions that lost billions to run up it’s debt? And, how can an institution award these bonuses necessary to pay people, right out of taxpayer money, if they aren’t willing to pay it back later? By definition, every dollar that flows into the pockets of employees can’t go back to the taxpayers whose money saved these same institutions. Once managers need to actually justify why they are paying people, due to the higher cost, I guarantee fewer employees will receive these higher bonuses. Gone will be the cuspy performers who are being paid because Wall St. is a creature of habit. This will create a wholesale re-thinking of compensation at many institutions. And, honestly, it’s long overdue. To be honest, I don’t really view this higher cost as excessive, either. People being paid 8-12% of profits (it’s actually revenue traders are compensated on, but don’t tell anyone that) should wind up actually costing 10%-20% of profits with this excess debt, perhaps as high as 30%–but these employees continue to be employed and able to profit due to taxpayer funds to begin with. It’s time managers are required justify, to their boards and owners, why high compensation for various employees is necessary. And, since companies say a surtax or banning of bonuses is bad and bonuses are absolutely required, they should be more than willing to pay these higher rates–they need these people after all!