Today, in the Huffington Post, I posted a document that shows an earlier incarnation of the ABACUS trade (although, not that different from the one that has got the SEC up in arms). I also explained it as well as I could. Head on over and let me know what you think.

Posted tagged ‘Goldman Sachs’

Inside Goldman’s ABACUS Trade

April 19, 2010Charlie Gasparino Still Doesn’t Understand

January 5, 2010I recently wrote a piece about Goldman Sachs an took issue with some things Charlie Gasparino had said. He felt it was necessary, then, to write something about m article, but not really respond to it. It should come as no surprise that Mr. Gasparino’s response is as devoid of content as his original piece. I go through it here, line by line (my responses are in bold):

Why a Business Writer Wishes Wall Street Wasn’t Such a Big Story

Could it be because of the scrutiny that now is focused on the author of this missive?

I’ve been covering Wall Street now for nearly 20 years, and it’s been a pretty good run. I’ve broken some big stories and written three books about the “Street,” and I’m looking to write another. I’ve made some friends along the way — people like Teddy Forstmann, the great investor who called the junk-bond crisis and had the insight to steer clear of several others, and I’ve made some enemies, namely the traders and bankers who work at many of the big firms who would have preferred I kept silent about their problems during last year’s financial crisis rather than blab about them on CNBC.

I find this the source the mainstream media’s greatest power and the cause of their greatest weaknesses. Notice that Mr. Gasparino makes his success a function of how many stories he has broken. Did he get them right? Well, given his propensity to report gossip, merely skim the surface, and follow the meme of the day when giving his opinion, perhaps he’s just picking the most favorable metric.

The story about Wall Street is a big one — and I’m afraid to say, it’s going to get bigger in 2010 and beyond. If you want to know why the federal government allows all those community banks to fail, but bails out Citigroup, Bank of America, etc., with unlimited funding, it’s because these institutions have grown so large, and become so important and intertwined in the global financial system, that letting them fail would be catastrophic. In other words, it’s cheaper to guarantee Citigroup’s survival (and that of Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, JP Morgan) with hundreds of billions of dollars in bailout money as the government did last year, than watch the global banking system implode.

Honestly, I have no problem with this paragraph’s message. Too big to fail is a true problem and it evokes a lot of populist rage. I’m inclined to question his motives for putting this here, but I’m going to give him the benefit of the doubt (there’ll be plenty of opportunity to pick on actual errors, faulty logic, and cherry-picking later).

Now you may think I just can’t wait to cover this story in 2010. Of course, the journalist in me says, “bring it on”: another book and columns to write, big stories to cover. But the American citizen in me makes me wish Wall Street wasn’t such a big story, that people like Vikram Pandit of Citigroup and Lloyd Blankfein of Goldman Sachs (yes, the guy who thinks trading bonds is “God’s Work”) just weren’t such a big part of American life that the country’s economy rises and falls on their bad bets.

This last part makes no sense at all. So, American citizens merely want the media to stop covering Wall St. or cover it less? And it’s because Goldman and Citi are big parts of the “American life” that the economy rises and falls on their bad bets? In the interest of being charitable, I’ll just assume that he meant to say that he wishes that the events causing the story weren’t as severe as they have turned out to be and that the problems, not just the focus wasn’t all that big. You’re welcome Charlie.

I’ve come to this conclusion after reading two articles. One is a thoughtful but at bottom unrealistic piece written by several HuffPost contributors, including Arianna Huffington. It proposes that Americans remove their money from the large money-center banks at the center of the reckless risk taking that led to last year’s meltdown and bailouts, and move their deposits into community banks, the good guys of finance that didn’t take the risk because they weren’t Too Big To Fail.

Interesting that he likes this piece, but thinks it’s unrealistic. It’s like damning with faint praise. I also think he needed an article to say something positive about, so why not the one written (at least partially) by the person who distributes his writing to the masses?

The other is a less thoughtful post written by an anonymous blogger also on this site that defends Goldman Sachs and questions some of my reporting, including one piece from The Daily Beast that suggests Goldman’s all-too-obvious image problems have begun to impact its investment banking business.

Ahhhh… and here it is. My piece is being called less thoughtful by Charlie Gasparino? That’s like me calling a fish a bad swimmer. Further, he says that I defend Goldman Sachs. Can we all pause for a moment and reread the headling of the post, written by me, that he cites? It is, “2010 Will be Challenging for Goldman Sachs”–how he translates my thesis, that next year will be an uphill battle for Goldman, as defending Goldman is still totally unbelievable to me. As a matter of fact, it implies that he doesn’t understand the piece at all. Now that, I believe.

As for his questioning my conclusion that there is no evidence that Goldman’s investment banking business has been materially hurt by their image problems, well… I cite the league tables in the original article. Further, this shouldn’t even matter all that much since such a large percentage of Goldman’s profits come from their trading and principal investing (again, in the numbers, and the exact point of my article).

What I like about Arianna’s piece is that it attempts to hold the bad guys responsible. Its point is pretty simple: The likes of Citigroup and Bank of America don’t deserve our money, so let’s hit them hard and reward those who deserve our support, namely the community banks, who, despite many failures, didn’t engage in massive risk taking as the so-called large “money center” banks did over the past decade. The problem with the piece is twofold: First, community banks weren’t blameless in terms of risk taking and thus aiding and abetted the real estate bubble, which is the root cause of our economic problems. That’s why so many of them have failed and will continue to do so. Also, by making smaller community banks more important we might simply transfer the policy and status of Too Big To Fail to a different set of institutions. Armed with government support and subsidy from the Too Big To Fail precedent, what would stop community banks from taking excessive risk just as Citi has done?

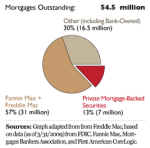

This paragraph is just silly. So, community banks are going to create hundreds of billions of dollars in CDOs? Could it be that smaller banks have failed because credit froze and they don’t have sophisticated hedging operations? Could it be that small banks have failed because they have loans as their primary assets and when the economy begins to have problems less people pay back their loans and banks take losses? Or, it could just be because they aided the real estate bubble. Although… Let’s take a look at this graphic from this ProPublica story (chopped a bit by me):

(Click for a larger version.)

Oh, right… If a small, community bank owns some mortgages, it means those mortgages weren’t securitized, and, thus, weren’t part of the massive overhang of toxic CDO assets that were made up of securitized mortgages. Finding this information cost me approximately five minutes on Google.

There are almost too many ways to attack the posting from the anonymous blogger (who goes by the name “Dear John Thain”), titled “2010 Will be A Challenging Year for Goldman Sachs,” (this guy obviously has a flair for understatement) so I will make the following points.

My comments will be more frequent now, as he’s getting to the good stuff. So far, all he says is (1.) the problems with my “posting” are numerous and (2.) I understated the problem in my title. He also promises to make multiple points…

Because he’s anonymous, we don’t know if he’s a Goldman executive (one way Goldman is now looking to attack its critics is by blogging positively about the firm, I am told) an investor with holdings of Goldman Sachs stock (a substantial conflict of interest if this is true), or just some guy with too much time on his hands.

This part is stupid, baseless, and implies Mr. Gasparino is backed into a corner. First, let me end this discussion now and forever by making the following statement: I am not now, nor have I ever been, an employee of Goldman Sachs or any of its subsidiaries. Further, I own no financial interest in Goldman or any of its subsidiaries. Second, I dare Mr. Gasparino to produce one shred of evidence, a comment on the record, or anything else indicating that Goldman is indeed using bloggers to defend them (Mr. Gasparino apaprently defines “blogging positively” as pointing out that Goldman almost certainly can’t reproduce its strong 2009 in 2010, as I did).

Beyond the mere infirm grasp of reality, this is where I think everyone who likes the blogosphere keeping the mainstream media honest, and indeed the blogosphere itself, should be deeply offended by what Mr. Gasparino has done. Mr. Gasparino has resorted to a sort of McCarthyism where insinuating someone who doesn’t wish to divulge their own identity is planted her by Goldman–a firm better known for suing bloggers than spawning them. This is insulting and should not be tolerated by any thinking person. The people who know the most about finance are the people who work in it. I make zero dollars from my blog and my writing. So many others risk their futures and livelihoods by writing, only to explain what is actually going on to those that are interested.

In fact, Charlie Gasparino, and his ilk, are the reason we exist. If he didn’t have the accuracy of a backfiring gun when it comes to issues other than gossip we, the pseudonymed finance writers, wouldn’t be needed. The public would understand financial topics much better and the record wouldn’t need to be set straight by those in the know. And now, when faced with someone correcting him on the record, he merely wishes to dismiss the facts and figures put before him and insinuate something for which he has no facts. Honestly, this speaks volumes about his regard for the truth and his ability to justify his own words when challenged.

This sort of attack should be rebuked as swiftly and sternly as it was introduced.

In any event, one line caught my eye: He takes issue with my assertion that Goldman benefits from a subsidy from the government because of its status now as a bank; he says it’s really a “financial holding company” as opposed to a “bank holding company” but fails to point out that there’s really no difference.

Honestly, Mr. Gasparino should either stop saying patently false things and merely learn to read. There is a major difference. Banks have stringent capital requirements. Financial holding companies do not. Let me pose a simple question, keeping in mind the distinction I just made. Is a financial holding company that owns a bank and a broker-dealer (the broker-dealer having a $1 trillion balance sheet) the same as being a bank with a $1 trillion balance sheet? Absolutely not. Banks cannot own certain sorts of assets, don’t have trading portfolios that need to marked to market every day, and are severely limited in terms of how much leverage they can take on. A broker-dealer, however, can take much riskier positions, can be more leveraged, and have different accounting rules (in addition to costs of funding). Mr. Gasparino did get one thing right, I failed to point out something that was patently false.

In the aftermath of the financial meltdown and bailout, Goldman is now primarily regulated by the Fed (as opposed to the Securities and Exchange Commission), the banking system’s chief regulator, and receives along with that all the benefits of the classification, including being treated in the market as Too Big To Fail, and thus being able to borrow cheaply.

Goldman the “financial holding company” is regulated by the Fed. Goldman’s bank is regulated by bank regulators. Goldman’s securities businesses are regulated by securities regulators. This is why people working inside large “financial supermarket” institutions have heard the expression “bank chain vehicle” and similar terms, the regulator for a specific division matters.

Here’s another fun fact that shows Mr. Gasparino has no idea what is saying: Goldman Sachs has had cheaper costs of borrowing (as shown by their credit default swaps) than Citi, the ultimate example of being way too big to exist.

As I pointed out in my book The Sellout, there’s much to admire about Goldman and its history in risk taking compared with the other big firms; this was, of course, the only firm to question its own irrational exuberance and short the subprime real estate market back in late 2006 (a trade in which a firm makes money if prices decline) whiles it competitors were betting bigger on the bubble. But that hedge only delayed the inevitable — Goldman, like the rest of the financial business (except maybe JP Morgan), bet big and wrong, so wrong that by the fall of 2009 it, along with most of its competitors, was falling into insolvency.

Fall of 2009? So, I guess the billions in profit Goldman reported for the third quarter of 2009 was all smoke and mirrors. Maybe he means 2008? Or maybe he’s more confused about what he wrote than I am.

All of which brings me to the bigger point of this piece: We as journalists, as commentators, and policy makers spend way too much time arguing over the fine points of Goldman’s status as a bank holding company or a financial holding company. Lloyd Blankfein is pilloried for saying he does God’s Work when he trades stocks or bonds, when in a more perfect world, what he says or what he does just shouldn’t mean that much to the guy who owns an auto repair shop in Queens or the family farmer in Iowa.

Charlie Gasparino, lumping himself in with policy makers, is being charitable. I want the people who make the law to argue over whether or not certain institutions should be allowed to employ certain types of corporate structures. I want the actual facts to be part of the public discourse and guide policy. Given the errors Mr. Gasparino tends to make, I can see why arguing over the specifics wouldn’t hold much appeal.

That’s why I kind of like Arianna’s idea (despite its drawbacks) of empowering community banks as opposed to the money center banks that are way too important and powerful and whose leaders just shouldn’t wield that type of influence because at bottom they’re just not smart enough — nor, perhaps, is anyone. Dear John Thain’s nom de plume is a reference, of course, to the former CEO of Merrill Lynch John Thain, who by all accounts didn’t think twice about spending more than $1 million decorating his office during the financial crisis, including tens of thousands on a high-end commode.

Make no mistake, the reference to John Thain “tricking out” his office has no place in the discussion. If Mr. Gasparino can’t take the time to read my About page, then at least he did as much research on me as he did for his actual articles.

To be sure, bankers have always wielded enormous power in our society — JP Morgan was a real person, after all. But somehow the importance of people like John Thain (whose spending spree also included a $1,400 parchment paper waste basket) and Lloyd Blankfein has grown beyond anyone’s comprehension, even their own. When former Lehman Brothers CEO Dick Fuld was rebuffing offers to buy his firm before its free fall into bankruptcy last year, I don’t think he truly envisioned the power of his inaction: That the entire financial system would shut down as a consequence of holding out for more money. One of the great lessons of the financial crisis is that this power was bestowed on the wrong people — the people who helped foment the housing bubble (along with the government) by packaging all those risky mortgages into allegedly safe bonds and then took so much risk that they destroyed the financial system and created the Great Recession and with it 10 percent unemployment.

Amazing. Once again he references John Thain’s excessive decorating budget. This is about as useful as me accusing Mr. Gasparino of being a murderer because his first name is the same as Charlie Manson. The other points in the paragraph are actually true: financial C.E.O.’s have a lot of power and have a huge impact on our financial system. This is why their industry is heavily regulated. The ending of his rant, about “the wrong people” and all that, is nonsense and vague. I’d dissect it further, but I’m tired.

It would be nice if in the not so distant future the Dick Fulds and Lloyd Blankfeins of the world become less important, even if I lose a book deal in the process.

I, too, think it would be nice if Mr. Gasparino had less of an opportunity to be in the public eye. But then again, I bet you already knew that.

Why 2010 will be Challenging for Goldman Sachs

December 30, 2009I figured I’d let 2009 go out with a bang and post another of my contrarian views: 2010 will be rough for Goldman Sachs. Why? Well, to know the answer to that, you should head on over to the Huffington Post where the full piece is online.

Happy New Year!

Maybe Charlie Gasparino is Too Simple to Grasp The Obvious

August 10, 2009Yes, that’s right… The guy whose only role, as far as I can tell, is to parrot back gossip, rumors, and “trial balloons” from P.R. people and executives has gone and proved that he is as irrelevant as he seems to be uncomplex. Did you read his attack on Matt Taibbi’s “piece” on Goldman Sachs? Well, I did… and I bled IQ points from doing so. Here’s where Mr. Gasparino shows his inability to reason:

It’s one thing to watch half-literate bloggers in desperate need of attention jump on the Goldman is the root of all evil story; it’s quite another to see respected news organizations with experienced reporters and presumably more experienced editors do it and in the process obscure the fact that Goldman, for all of its sins during the bubble years, was probably the least culpable for the system’s eventual collapse.

(Emphasis mine.)

Oh, and Mr. Gasparino is (highly, highly ironically!) writing this in a section entitled “Blogs and Stories”–since Gasparino’s post/article/whatever falls far short of the reasoned, cogent, logical, and expertise-based sorts of things one gets from the the blogosphere, I’ll let you decide which of these two headings applies to his writing.

Writing a particular piece of drivel and attacking the blogosphere isn’t all that bad in the grand scheme of things–it is, however, a good reason people should stop reading what he says and watching his appearances on air (and people are doing just that). More damning is Mr. Gasparino’s inability to see that he is a major part of the problem. If he went even the slightest bit beyond the drivel he usually passes off as reporting (aforementioned gossip, rumors, and “trial balloons”) he might have been able to educate people to the point where they wouldn’t buy into hyperbole-laden articles. Mr. Taibbi’s job isn’t to be a journalist and provide a fair and dispassionate accounting of the facts–he even says as much:

I’m aware that some people feel that it’s a journalist’s responsibility to “give both sides of the story” and be “even-handed” and “objective.” A person who believes that will naturally find serious flaws with any article like the one I wrote about Goldman. I personally don’t subscribe to that point of view. My feeling is that companies like Goldman Sachs have a virtual monopoly on mainstream-news public relations; for every one reporter like me, or like far more knowledgeable critics like Tyler Durden, there are a thousand hacks out there willing to pimp Goldman’s viewpoint on things in the front pages and ledes of the major news organizations.

(Emphasis mine.)

(By the way, Mr. Gasparino says what amounts to the same thing: “I have to admit I love to beat up on Goldman; I do it for The Daily Beast and on CNBC every chance I get.”)

Mr. Taibbi’s job is to get page views and tell a story. He even admits that members of the blogosphere (Tyler Durden being a reference to the blog whose traffic has experienced a meteoric rise–Zero Hedge) have a better grasp of whats actually going on than he does. I would hope, for example, that most bloggers wouldn’t make the mistake (I’m being about as charitable as one can be by not calling it “lying” or “misleading” or “taking advantage”) of confusing leverage with VaR as Mr. Taibbi does. Mr. Taibbi, in that same piece, also glosses over technical details of primary dealers of treasury securities (I wonder if he understands bid-to-cover and direct versus indirect) and nuances of equity underwriting (What sort of limits are in place for fees? How does a greenshoe work? What does an investment banker do versus an equity capital markets person? What about a syndicate person?). In his original piece, there is a ton of faulty reasoning and thin (well, mostly non-existent, actually … mostly the reasons for things or support are “because I say so”) evidence for his theories. But, who’s to know? The public knows almost nothing about how the financial system works.

Which brings me back to my original point–Charlie Gasparino is to blame for Matt Taibbi’s drivel. Not solely, obviously, but he is a very public face of a very dumbed-down financial media that is the personification of the phrase, “Couldn’t find his ass with both hands.” If Mr. Gasparino and the financial media can’t report on the markets and financial system reasonably–and instead dumb down their reports, thus helping feed the financial illiteracy of the mainstream public–then he has allowed Matt Taibbi’s piece to gain traction in the minds of the public, not the bloggers. He and his colleagues have completely failed in their charge: to keep the public well-informed when it comes to matters of finance and markets.

If Charlie Gasparino had even the slightest bit of a clue, or if even the most modest degree of intelligence was peeking through his rants and gossip column style of reporting, he might understand that blogosphere should be his friend and best resource. Where else can anyone get a peek into the extremely technical, often changing worlds of trading, banking, finance, etc.? You literally have dozens of people who are giving away their domain expertise for free (anonymous authors–the brave, intrepid, good-looking genius champions of truth and justice that they are [hyperbole included at no extra cost]–don’t even take credit for their work, they are doing it for themsevles and their readers solely!). Mr. Gasparino (and other CNBC personalities whose brains seem to be disconnected during the day to conserve energy–go to the link, but don’t watch the clip, you’ll start spilling IQ points all over the floor) should be looking to these bloggers to help him understand complex issues that it would take years of experience to understand, give him ideas for how to report on an issue and explain the nuances, and even as sources that he can cite to increase the authority of his conclusions.

But, of course, this “get information from where information lives” approach to journalism completely escapes the financial media (I’ve explained how problems like this can be fixed before). Mr. Gasparino prefers, instead, to refer to bloggers as “half-literate” and thinks New York Magazine, because it’s a “respected news organization” (Of course! When I think of the news I think of New York Magazine!), will do a better job than the people in the trenches every day. This is why finance is the reverse of every other major news category I can think of–usually the primary value of the mainstream media is to dig up facts and write complex stories (that show cause and effect or intricate interconnections) while the blogosphere adds a layer of gossip, conjecture, spin, and/or analysis. In finance, the complex picture gets painted by the blogs and the mainstream media reports singular, one-dimensional little tidbits (think, “Chuck Prince gets fired!” or “Goldman Reports profits for this quarter!”). The notable exceptions are some of the detailed timelines published by the WSJ (like Kate Kelly’s three part Bear Stearns article) and a large swathe of the content from Dealbook (Is it a coincidence that Dealbook has bloggers writing for it and contains both the single fact/headline-driven articles as well as detailed analysis and complex reporting? Nope. Although, the reporting done for much of the longer articles isn’t blogger driven.).

In fact, keeping with the clueless theme, Gasparino directly addresses some of Taibbi’s conjecture, attempting to disprove some of the moreimflamatory claims:

Okay, sure, maybe there’s some evidence somewhere proving that the entire regulatory apparatus of the Fed run by an appointee of a Republican president, Ben Bernanke, to the Treasury Department run by a lifelong Republican (Paulson once worked for Richard Nixon) … would drop everything to save Goldman Sachs[.] … But if there is good evidence to that effect, I haven’t seen it. A more plausible explanation for the Goldman bailout via AIG’s bailout (borne out by my reporting for my upcoming book The Sellout) goes something like this: There was panic in Paulson’s office … not because they saw their retirement money tied up in Goldman stock ready to disappear, but because after Lehman fell, the other dominoes would be teetering.

(Emphasis mine.)

Whew! With an expert reporter like Mr. Gasparino on the case (including the reporting he has done for his book), then if he hasn’t seen any evidence, who has? Oh, right, the New York Times:

During the week of the A.I.G. bailout alone, Mr. Paulson and Mr. Blankfein spoke two dozen times, the calendars show, far more frequently than Mr. Paulson did with other Wall Street executives.

On Sept. 17, the day Mr. Paulson secured his waivers, he and Mr. Blankfein spoke five times. Two of the calls occurred before Mr. Paulson’s waivers were granted. […]

But Mr. Paulson was closely involved in decisions to rescue A.I.G., according to two senior government officials who requested anonymity because the negotiations were supposed to be confidential.

And government ethics specialists say that the timing of Mr. Paulson’s waivers, and the circumstances surrounding it, are troubling. […]

While that agreement barred him from dealing on specific matters involving Goldman, he spoke with Mr. Blankfein at other pivotal moments in the crisis before receiving [conflict of interest] waivers.

Mr. Paulson’s schedules from 2007 and 2008 show that he spoke with Mr. Blankfein, who was his successor as Goldman’s chief, 26 times before receiving a waiver. […]

At the height of the financial crisis, Mr. Paulson spoke far more often with Mr. Blankfein than any other executive, according to entries in his calendars. […]

According to the schedules, Mr. Paulson’s contacts with Mr. Blankfein began even before the height of the crisis last fall. During August 2007, for example, when the market for asset-backed commercial paper was seizing up, Mr. Paulson spoke with Mr. Blankfein 13 times. Mr. Paulson placed 12 of those calls.

By contrast, Mr. Paulson spoke six times that August with Richard S. Fuld Jr. of Lehman, four times with Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase and only twice with John Thain of Merrill Lynch.

Seems like a pretty clear pattern that strikes right at the heart of the matter. I’m sure it was just bad luck for Mr. Gasparino that the one place he tried to move the conversation into a more rational zone, and also the one point he used to show why his upcoming book has any value at all, was the place more professional news outlets actually did some serious reporting and proved him naive. The Times’ piece doesn’t prove beyond a reasonable doubt, conclusively, or to any other standard one would like to use that what Taibbi alleges occurred, but its pretty good evidence that Hank Paulson conducted himself in a way that is questionable ethically. Well, don’t forget that Mr. Gasparino has a better theory in his book–which you can pre-order for $27.99! What’s this magical book about? From the Amazon description:

[Gasparino] shows how and why several of these storied institutions have suffered staggering losses in assets and influence since [2002], triggering the vast financial crisis that is now devastating individual and institutional wallets through the United States and across the globe. Gasparino is known as a dogged reporter who regularly breaks news about Wall Street’s inner workings and who has a direct line into Wall Street’s most prominent dealmakers. His book promises to be one of the first books out of the gate in what will prove to be a crowded market of ‘financial crisis’ books, but his talent for delivering a dramatic narrative and colorful anecdotes and explaining complex financial maneuvers in accessible terms.

(Emphasis mine.)

Actually, instead of spending $27.99 on this book, by the guy who didn’t see any evidence of something the New York Times found significant evidence of (now that its published, maybe he’ll see it … when he reads the Times), you can just read blogs to understand “how and why several of these storied institutions have suffered staggering losses in assets and influence.” You’ll understand it better when you’re done and the information you read has a much, much higher probability of being both correct and complete. Oh, and reading a blog is free…

P.S. Maybe I’ll write a point by point refutation of Taibbi and Gasparino’s remaining arguments at some point… But please don’t think that because the Times found some evidence consistent with what Taibbi alleged that he is correct. Stopped watch and all that.

A Recounting of Recent History

July 28, 2009Yes, I’m alive! I’m terribly sorry for the extended silence, but I’ve had some big changes going on in my personal life and have been out of the loop for a while (honestly, my feed reader needs to start reading itself–I have over 1,000 unread posts when looking at just 4 financial feeds). So, here’s what I haven’t had a chance to post…

1. I totally missed the most recent trainwreck of a P.R. move at Citi. There is so much crap going on around Citi… I really intend to write a post that is essentially a linkfest of Citi material that stitches together the narrative of how Citi got into this mess and how Citi continues to do itself no favors. There was also a completely vapid opinion piece from Charlie Gasperino that said absolutely nothing new, save for one sentence, and then ended with a ridiculous comparison that was clearly meant to generate links. I’m not even going to link to it… It was on the Daily Beast, if you must find it.

2. I haven’t really had the opportunity to comment on the Obama administration’s overhaul of the financial regulatory apparatus. Honestly, it sucks. It doesn’t do much and gives too much power to the Fed. You’d think that after that recent scandal within the ranks of the Fed there would be a political issue with giving it more power. Even more interestingly, all other major initiatives from the Obama administration have been drafted by congress. Here, the white paper came from the Whitehouse itself. That won’t do too much to quiet the critics who are claiming that the Whitehouse is too close to Wall St. Honestly, if one is to use actions instead of words to measure one’s intentions, then it’s hard to point to any evidence that the Obama administration isn’t in the bag for the financial services industry.

3. The Obama administration did an admirable job with G.M. and Chrysler. They were both pulled through bankruptcy, courts affirmed the actions, and there was a minimal disruption in their businesses. Stakeholders were brought to the table, people standing to lose from the bankruptcy, the same people (I use that word loosely–most are institutions) who provided capital to risky enterprises, were forced to take losses, and the U.S.A. now has something it has never had: an auto industry where the U.A.W. has a stake and active interest in the companies that employ its members. Perhaps the lesson, specifically that poorly run firms that need to be saved should cause consequences for the people who caused the problems (both by providing capital and providing inadequate management), will take hold in the financial services sector too–I’m not holding my breath, though.

4. Remember this problem I wrote about? Of course not, that is one of my least popular posts! However, some of the questions are being answered. Specifically, the questions about how and when the government will get rid of its ownership stakes, and at what price, are starting to be filled in. It was rather minor news when firms started paying T.A.R.P. funds back. However, the issue of dealing with warrants the government owns was a thornier issue. Two banks have dealt with this issue–Goldman purchased the securities at a price that gives the taxpayers a 23% return on their investment and JP Morgan decided that it would forgo a negotiated purchase and forced the U.S. Treasury to auction the warrants.

On a side note: From this WSJ article linked to above, its a bit maddening to read this:

The Treasury has rejected the vast majority of valuation proposals from banks, saying the firms are undervaluing what the warrants are worth, these people said. That has prompted complaints from some top executives. […] James Dimon raised the issue directly with Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, disagreeing with some of the valuation methods that the government was using to value the warrants.

(Emphasis mine.)

If I were on the other end of the line, my response would be simple: “Well, Jamie, I agree. The assumptions we use to value securities here at the U.S. government can be, well … off. So, we’ll offer you what you think is fair for the warrants if you’ll pay back the $4.4 billion subsidy we paid when we initially infused your bank with T.A.R.P. funds.” Actually, I probably would have had a meeting with all recipients about it and quoted a very high price for these warrants and declared the terms and prices non-negotiable–does anyone really think that, in the face of executive pay restrictions, these firms wouldn’t have paid whatever it would take to get out from under the governments thumb? As long as one investment banker could come up with assumptions that got the number, they would have paid it. Okay, that’s all for my aside.

5. I’m dreadfully behind on my reading… Seriously. Here’s a list of articles I haven’t yet read, but intend to…

- The Science of Economic Bubbles and Busts — A scientific look at bubbles, specifically the psychology.

- Sheila Bair, FDIC, and the financial crisis — A profile of Sheila Bair. I find the New Yorker profiles very good and nearly impossibly long.

- Rich Harvard, Poor Harvard: Vanity Fair — An interesting look at Harvard and how its fortunes interplay with its endowment and its in-house money manager.

- Prophet Motive — A profile of Nouriel Roubini. My gut tells me he’s a case study in being more lucky than right, but I haven’t read it, so who knows.

- The Way We Live Now – Diminished Returns — A NY Times article whose title makes too much sense to pass up!

- Confessions of a Bailout CEO Wife — As close as I’ll ever get to US Weekly.

- What Does Your Credit-Card Company Know About You? — Ugh. My gut tells me too much. As a Consumerist reader, I think I know what this is, but we’ll see.

- At Geithner’s Treasury, Key Decisions on Hold — An article that got a lot of play as a good case study.

- Paulson’s Complaint — Paulson claiming Lehman didn’t cause the huge problems in the markets and economy that followed its bankruptcy. I don’t buy it.

- The Crisis and How to Deal with It — A weird multi-person article in the New York Review of Books.

- The New York Fed is the most powerful financial institution you’ve never heard of. Look who’s running it — A Slate article by Eliot Spitzer. I admit to not really get the Fed system.

- Tracking Loans Through a Firm That Holds Millions — A look at a servicer, I believe.

- Flawed Credit Ratings Reap Profits as Regulators Fail — Wow. Based on the title, I must have dangerously low blood pressure that needs boosting!

- The formula that felled Wall St — Another look at Gaussian Copula, I think. Felix, also looked at this.

- Peter Orszag and the Obama budget — Another New Yorker profile.

- Geithner, Member and Overseer of Finance Club — A NY Times profile of Tim.

- HMC Tax Concerns Aided Federal Inquiries — Interestingly, an article that got national press, is an investigative piece, and deals with finance from a college newspaper!

- Treasury Chief Tim Geithner Profile –Portfolio profile of Tim. I’ll know everything about him by the end of this list.

- Lewis Testifies U.S. Urged Silence on Deal — I really don’t know about this situation. I want to read up and understand all the details.

- The Wail of the 1% — Honestly, not sure. Talking about the plight of the rich?

- Economic View – Why Creditors Should Suffer, Too — The title makes me want to read this. Confirmation bias, perhaps?

- How Bernanke Staged a Revolution — A profile of Ben Bernanke by the WaPo.

- 5 Ways Companies Breed Incompetence — Just five?

- Ten principles for a Black Swan-proof world — An opinion piece from the FT by Nassim Nicholas Taleb.

- A New Era for Financial Regulation — Megan McArdle looks at the proposed regulatory structure. Honestly, I don’t read her, so I’m skeptical about this piece.

- U.S. Plan to Stem Foreclosures Is Mired in Paper Avalanche — Not sure. One of the longer NY Times pieces.

- Bill Gross of Pimco Is on Treasury’s Speed Dial — A profile of Pimco’s role in fixing the financial problems, conflicts, etc.

- Congress Helped Banks Defang Key Rule — Another fix for low blood pressure.

- Timothy Geithner and Lawrence Summers – The Case for Financial Regulatory Reform — OpEd by Geithner and Summers.

- SEC Chief Strives To Rebuild Regulator — An article on the problems at the S.E.C.

- A Daring Trade Has Wall Street Seething — A writeup of how a small firm worked the system to make money. Should be interesting.

- President’s Economic Circle Keeps Tensions at a Simmer — An interesting case study on how Obama’s economic team works.

- Back to Business – Banks Dig In to Resist New Limits on Derivatives — Hey! We’re paying banks to spend money to lobby ourselves to not regulate them so they can profit off of our money! Sweet!

I hope to get more time to post in the coming days. Also, I am toying with the idea of writing more frequent, much shorter posts. On the order of a paragraph where I just toss out a thought. Not really my style, but maybe it would be good. Feedback appreciated.

Guest Post at Clusterstock

April 23, 2009Hey, I wanted to let you, my loyal readers, know that I guest posted over at Clusterstock. The post, entitled “Investment Bank Scorecard” is my take on this past quarter as a whole. I think it’s worth clicking over and taking a look. I’d sum it up here, but, in all honesty, the value is in the nuances and small insights more than the general thesis.

Also, here is the chart attached to that post, in its orginal form.

Repaying T.A.R.P.: There Are Restrictions

April 21, 2009There is a meme (did you know that word was invented by Richard Dawkins?) going around the blogosphere that, in essence, says Geithner doesn’t have the right to prevent T.A.R.P. repayment, even if no fresh capital is raised. This is incorrect. From the Goldman Sachs T.A.R.P. agreements [pdf!] governing the capital infusion (it’s hidden on the site, but there!):

(Emphasis [yes, that’s the green underlining] mine.)

Seems, then, that it’s pretty clear. Whole or partial payments, once allowed by a regulator, require fresh equity raised from a “Qualified Equity Offering.” This is a defined term, and the document defines it as follows:

So, it seems pretty cleat that there are conditions. Now, maybe these aren’t the systemic considerations, but that’s likely why the regulatory approval is required, especially in conjunction with the “stress test,” which we’ve discussed here at length.

Citi’s Earnings: Even Cittier Than You Think

April 20, 2009Well, Citi reported earnings this past week. And, as many of you know, there are a few reasons you’ve heard to be skeptical that this was any sort of good news. However, there are a few reasons you probably haven’t heard… (oh, and my past issues on poor disclosure are just as annoying here)

On Revenue Generation: First, here are some numbers from Citi’s earnings report and presentation, Goldman’s earnings report, and JP Morgan’s earnings report:

These numbers should bother Citi shareholders. Ignoring the 1Q08 numbers, Citi–whose global business is much larger and much more diverse than it’s rivals–generates no more, if not slightly less, revenue than the domestically focused JP Morgan and much, much less than Goldman. But it gets worse. Goldman’s balance sheet was $925 billion vs. Citi’s $1.06 trillion in assets within it’s investment banking businesses, roughly 10% larger. I’d compare JP Morgan, but they provide a shamefully small amount of information. As an entire franchise, however, Citi was able to generate their headline number: $24.8 billion in revenue, on assets of $1.822 trillion. JP Morgan, as a whole, was able to generate $26.9 billion, on assets of $2.079 trillion. JP Morgan, then is 14% larger, by assets, and generstes 8% higher revenue.

These numbers should be disconcerting to Citi, it’s no better at revenue generation than it’s rivals, despite having a larger business in higher growth, higher margin markets. Further, in an environment rife with opportunity (Goldman’s results support this view, and anecdotal support is strong), Citi was totally unable to leverage any aspect of it’s business to get standout results… and we’re only talking about revenue! Forget it’s cost issues, impairments and other charges as it disposes assets, etc.

On The Magical Disappearing Writedowns: Even more amazing is the lack of writedowns. However, this isn’t because there aren’t any. JP Morgan had writedowns of, approximately, $900 million (hard to tell, because they disclose little in the way of details). Goldman had approximately $2 billion in writedowns (half from mortgages). Citi topped these with $3.5 billion in writedowns on sub-prime alone (although they claim only $2.2 billion in writedowns, which seems inconsistent). But, that isn’t close to the whole story. Last quarter, in what I could find almost no commentary on during the last conference call and almost nothing written about in filings or press releases, Citi moved $64 billion in assets from the “Available-for-sale and non-marketable equity securities” line item to the “Held-to-maturity” line item. In fact, $10.6 billion of the $12.5 billion in Alt-A mortgage exposure is in these, non–mark-to-market accounts. There was only $500 million in writedowns on this entire portfolio, surprise! Oh, and the non–mark-to-market accounts carry prices that are 11 points higher (58% of face versus 47% of face). What other crap is hiding from the light? $16.1 billion out of $16.2 billion total in S.I.V. exposure, $5.6 billion out of $8.5 billion total in Auction Rate Securities exposure, $8.4 billion out of $9.5 billion total in “Highly Leveraged Finance Commitments,” and, seemingly, $25.8 billion out of $36.1 billion in commercial real estate (hard to tell because their numbers aren’t clear), are all sitting in accounts that are no longer subject to writedowns based on fluctuations in market value, unlike their competitors. These are mostly assets managed off the trading desk, but marked according to different rules than traded assets. If one doesn’t have to mark their assets, then having no writedowns makes sense.

On The Not-so-friendly Trend: This is a situation where, I believe, the graphs speak for themselves.

Do any of these graphs look like things have turned the corner? Honestly, these numbers don’t even look like they are decelerating! Compare this with the (relatively few) graphs provided by JP Morgan.

These aren’t directly comparable, as the categories don’t correspond to one another, and JP Morgan uses the more conservative 30-day delinquent instead of Citi’s 90+-day delinquent numbers. However, JP Morgan’s portfolio’s performance seems to be leveling out and even improving (with the possible exception of “Prime Mortgages”). Clearly, the pictures being painted of the future are very different for these institutions.

On the Stuff You Know About: I’ll be honest, this business about Citi benefiting from it’s own credit deterioration was confusing. Specifically, there is more going on when Citi refers to “credit value adjustments” than just profiting from it’s own Cittieness. However, Heidi Moore, of Deal Journal fame helped set me straight on this–the other things going on are dwarfed by the benefit I just mentioned. Here’s the relevant graphic from the earnings presentation:

And, via Seeking Alpha’s Transcript, the comments from Ned Kelly that accompanied this slide:

Slide five is a chart similar to one that we showed last quarter which shows the movement in corporate credit spreads since the end of 2007. During the quarter our bond spreads widened and we recorded $180 million net gain on the value of our own debt for which we’ve elected the fair value option. On our non-monoline derivative positions counterparty CDS spreads actually narrowed slightly which created a small gain on a derivative asset positions.

Our own CDS spreads widened significantly which created substantial gain on our derivative liability positions. This resulted in a $2.7 billion net mark to market gain. We’ve shown on the slide the five-year bond spreads for illustrative purposes. CVA on our own fair value debt is calculated by weighting the spread movements of the various bond tenors corresponding to the average tenors of debt maturities in our debt portfolio. The debt portfolio for which we’ve elected the fair value options is more heavily weighted towards shorter tenures.

Notice that Citi’s debt showed a small gain, but it’s derivatives saw a large gain (the additional $166 million in gains related to derivatives was due to the credit of it’s counterparties improving). Why is this? Well, notice the huge jump in Citi’s CDS spread over this time period versus cash bonds, which were relatively unchanged. Now, from Citi’s 2008 10-K:

CVA Methodology

SFAS 157 requires that Citi’s own credit risk be considered in determining the market value of any Citi liability carried at fair value. These liabilities include derivative instruments as well as debt and other liabilities for which the fair-value option was elected. The credit valuation adjustment (CVA) is recognized on the balance sheet as a reduction in the associated liability to arrive at the fair value (carrying value) of the liability.

Citi has historically used its credit spreads observed in the credit default swap (CDS) market to estimate the market value of these liabilities. Beginning in September 2008, Citi’s CDS spread and credit spreads observed in the bond market (cash spreads) diverged from each other and from their historical relationship. For example, the three-year CDS spread narrowed from 315 basis points (bps) on September 30, 2008, to 202 bps on December 31, 2008, while the three-year cash spread widened from 430 bps to 490 bps over the same time period. Due to the persistence and significance of this divergence during the fourth quarter, management determined that such a pattern may not be temporary and that using cash spreads would be more relevant to the valuation of debt instruments (whether issued as liabilities or purchased as assets). Therefore, Citi changed its method of estimating the market value of liabilities for which the fair-value option was elected to incorporate Citi’s cash spreads. (CDS spreads continue to be used to calculate the CVA for derivative positions, as described on page 92.) This change in estimation methodology resulted in a $2.5 billion pretax gain recognized in earnings in the fourth quarter of 2008.

The CVA recognized on fair-value option debt instruments was $5,446 million and $888 million as of December 31, 2008 and 2007, respectively. The pretax gain recognized due to changes in the CVA balance was $4,558 million and $888 million for 2008 and 2007, respectively.

The table below summarizes the CVA for fair-value option debt instruments, determined under each methodology as of December 31, 2008 and 2007, and the pretax gain that would have been recognized in the year then ended had each methodology been used consistently during 2008 and 2007 (in millions of dollars).

Got all that? So, Citi, in it’s infinite wisdom, decided to change methodologies and monetize, immediately, an additional 290 bps in widening on it’s own debt. This change saw an increase in earnings of $2.5 billion prior to this quarter. In fact, Citi saw a total of $4.5 billion in earnings from this trick in 2008. However, this widening in debt spreads was a calendar year 2008 phenomenon, and CDS lagged, hence the out-sized gain this quarter in derivatives due to FAS 157 versus debt. Amazing.

And, while we’re here, I want to dispel a myth. This accounting trick has nothing to do with reality. The claim has always been that a firm could purchase it’s debt securities at a discount and profit from that under the accounting rules, so this was a form of mark-to-market. Well, unfortunately, rating agencies view that as a technical default–S&P even has a credit rating (“SD” for selective default) for this situation. This raises your cost of borrowing (what’s to say I’ll get paid in full on future debt?) and has large credit implications. I’m very, very sure that lots of legal documents refer to collateral posting, and other negative effects if Citi is deemed in “default” by a rating agency, and this would be a form of default. This is a trick, plain and simple–in reality, distressed tender offers would cost a firm money.

The Bottom Line: Citi isn’t out of the woods. In this recent earnings report I see a lot of reasons to both worry and remain pessimistic about Citi in the near- and medium-term. If you disagree, drop me a line… I’m curious to hear from Citi defenders.

Contrarian View: Goldman

September 17, 2008Goldman could be screwed? Surely I jest. Well, I would suggest that if Goldman thinks it can survive, it could wind up being the next firm to refuse to sell at the levels being offered. Also, who is left to acquire Goldman? Clearly a second-tier of potential acquirers with big balance sheets. Maybe private equity? HA! Imagine P.E. firms swooping in to take Goldman private. Amazing irony… Perhaps a sovereign wealth fund will swoop in.

Interesting thought: Could Goldman Sachs Capital Partners take Goldman Sachs private? Goldman Sachs has a market cap of about $45 billion right now… probably not, but with some trickery, who knows? A few more days like today, and the answer will be yes!