As the results of the stress test start leaking out slowly, it’s a fun exercise to make some educated guesses/predictions about what the future holds and take note of pertinent facts. As we’ve discussed before, there is a lot to take issue with when considering the results of the stress test at all, especially given the added layers of uncertainty stemming form the limited information provided in the scenarios. So, without further delay, let’s get started.

1. The baseline scenario will prove wholly inadequate as a “stress test.” Please, follow along with me as I read from the methodology (pdf). I’ll start with the most egregious and reckless component of the mis-named baseline scenario (I would rename it the, “if payer works” scenario) : what I will refer to as “the dreaded footnote six.” From the document:

As noted above, BHCs [(Bank Holding Companies, or the firms being stress tested)] with trading account assets exceeding $100 billion as of December 31, 2008 were asked to provide projections of trading related losses for the more adverse scenario, including losses from counterparty credit risk exposures, including potential counterparty defaults, and credit valuation adjustments taken against exposures to counterparties whose probability of default would be expected to increase in the adverse scenario.(6)

[…]

(6) Under the baseline scenario, BHCs were instructed to assume no further losses beyond current marks.

(Emphasis mine.)

Holy <expletive>! In what alternate/parallel/baby/branching universe is this indicative of anything at all? Assume no further losses beyond current marks? Why not assume everything returns to par? Oh, well, that actually was a pretty valid assumption for the baseline scenario. From the document:

New FASB guidance on fair value measurements and impairments was issued on April 9, 2009, after the commencement of the [stress test]. For the baseline scenario supervisors considered firms’ resubmissions that incorporated the new guidance.

(Emphasis mine.)

Thank goodness! I was worried that the “if prayer works” scenario might have some parts that were worth looking at. Thankfully, for troubled banks, I can skip this entire section. (Confidence: 99.9999%)

2. Trading losses will be significantly understated across all five institutions that will need to report them. First, only institutions with over $100 billion in trading assets were asked to stress their trading positions. Second, from the section on “Trading Portfolio Losses” from the document:

Losses in the trading portfolio were evaluated by applying market stress factors … based on the actual market movements that occurred over the stress horizon (June 30 to December 31, 2008).

(Emphasis mine.)

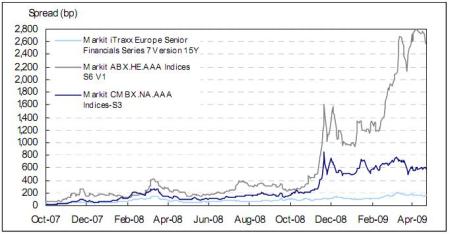

Okay, well, that seems reasonable, right? Hmmmm… Let’s take a look. Here is what some indicative spread movements for fixed income products looked like January 9th of 2009, according to Markit (who has made it nearly impossible to find historical data for their indices, so I’m resorting to cutting and pasting images directly–all images are from their site):

(Click on the picture for a larger version.)

Well, looks like a big move is taken into account by using this time horizon. Clearly this should provide a reasonable benchmark for the stress test results, right? Well, maybe not.

(Click on the picture for a larger version.)

Yes, that’s right, we’ve undergone, for sub-prime securities a massive widening during 2009 already. Also, as far as I can tell, the tests are being run starting from the December 2008 balance sheet for each company. So, if I’m correct, for the harsher scenario, trading losses will be taken on December 2008 trading positions using December 2008 prices and applying June 2008 to December 2008 market movements. For sub-prime, it seems pretty clear that most securities would be written up (June 2008 Spread: ~200, December 2008 Spread: ~1000, Delta: ~800, Current Spread: ~2600, December 2008 to Today Delta: ~1600, Result: firms would take, from December 2008 levels, half the markdown they have already taken).

Also, it should be a shock to absolutely no one that most trading assets will undergo a lagged version of this same decline. Commercial mortgages and corporate securities rely on how firms actually perform. Consumer-facing firms, as unemployment rises, the economy worsens and consumption declines, and consumers default, will see a lagged deterioration that will appear in corporate defaults and small businesses shuttering–both of these will lead to commercial mortgages souring. Indeed we’ve seen Moody’s benchmark report on commercial real estate register a massive deterioration in fundamentals. That doesn’t even take into account large, exogenous events in the sector. Likewise, we see consistently dire predictions in corporate credit research reports that only point to rising defaults 2009 and 2010.

In short, for all securities, it seems clear that using data from 2H2008 and applying those movements to December 2008 balance sheets should produce conservative, if not ridiculously understated loss assumptions. (Confidence: 90%)

3. Bank of America will have to go back to the government. This, likely, will be the end of Ken Lewis. It’s not at all clear that Bank of America even understands what’s going on. First, if I’m correctly reading Bank of America’s first quarter earnings information, the firm has around $69 billion in tangible common equity. Also, it should be noted that the FT is reporting that Bank of America has to raise nearly $34 billion. Now, with all this in mind, let’s trace some totally nonsensical statements that, unlike any other examples in recent memory, were not attributed to anonymous sources (from the NYT article cited above):

The government has told Bank of America it needs $33.9 billion in capital to withstand any worsening of the economic downturn, according to an executive at the bank. […]

But J. Steele Alphin, the bank’s chief administrative officer, said Bank of America would have plenty of options to raise the capital on its own before it would have to convert any of the taxpayer money into common stock. […]

“We’re not happy about it because it’s still a big number,” Mr. Alphin said. “We think it should be a bit less at the end of the day.” […]

Regulators have told the banks that the common shares would bolster their “tangible common equity,” a measure of capital that places greater emphasis on the resources that a bank has at its disposal than the more traditional measure of “Tier 1” capital. […]

Mr. Alphin noted that the $34 billion figure is well below the $45 billion in capital that the government has already allocated to the bank, although he said the bank has plenty of options to raise the capital on its own.

“There are several ways to deal with this,” Mr. Alphin said. “The company is very healthy.”

Bank executives estimate that the company will generate $30 billion a year in income, once a normal environment returns. […]

Mr. Alphin said since the government figure is less than the $45 billion provided to Bank of America, the bank will now start looking at ways of repaying the $11 billion difference over time to the government.

(Emphasis mine.)

Right around the time you read the first bolded statement, you should have started to become dizzy and pass out. When you came to, you saw that the chief administrative officer, who I doubt was supposed to speak on this matter (especially in advance of the actual results), saying that a bank with $69 billion in capital would be refunding $11 billion of the $45 billion in capital it has already received because they only need $34 billion in capital total. Huh? Nevermind that the Times should have caught this odd discrepancy, but if this is the P.R. face the bank wants to put on, they are screwed.

Now, trying to deal with what little substance there is in the article, along with the FT piece, it seems pretty clear that, if Bank of America needs $34 billion in additional capital, there is no way to get it without converting preferred shares to common shares. There is mention of raising $8 billion from a sale of a stake in the China Construction Bank (why are they selling things if they are net positive $11 billion, I don’t know). That leaves $26 billion. Well, I’m glad that “once a normal environment returns” Bank of America can generate $30 billion in income (Does all of that fall to T.C.E.? I doubt it, but I have no idea). However, over the past four quarters, Bank of America has added just $17 billion in capital… I will remind everyone that this timeframe spans both T.A.R.P. and an additional $45 billion in capital being injected into the flailing bank. Also, who is going to buy into a Bank of America equity offering now? Especially $26 billion of equity! If a troubled bank can raise this amount of equity in the current environment, then the credit crisis is over! Rejoice!

I just don’t see how Bank of America can fill this hole and not get the government to “bail it out” with a conversion. The fact that Bank of America argued the results of the test, frankly, bolsters this point of view. Further, this has been talked about as an event that requires a management change, hence my comment on Lewis. (Confidence: 80% that the government has to convert to get Bank of America to “well capitalized” status)

Notes/Odds and Ends:

1. I have no idea what happened with the NY Times story about the results of the “Stress Test.” The WSJ and FT are on the same page, but there could be something subtle that I’m misunderstanding or not picking up correctly. Absent this, my comments stand. (Also, if might have been mean.unfair of me to pick on the content of that article.)

2. The next phases of the credit crisis are likely to stress bank balance sheets a lot more. The average bank doesn’t have huge trading books. However, they do have consumer-facing loan and credit products in addition to corporate loans and real estate exposure. In the coming months, we’ll see an increase in credit card delinquencies. Following that, we’ll see more consumer defaults and corporations’ bottom line being hurt from the declining fundamentals of the consumer balance sheet. This will cause corporate defaults. Corporate defaults and consumer defaults will cause commercial real estate to decline as well. The chain of events is just beginning. Which leads me to…

3. Banks will be stuck, unable to lend, for a long time. I owe John Hempton for this insight. In short, originations require capital. Capital, as we see, is in short supply and needed to cover losses for the foreseeable future. Hence, with a huge pipeline of losses developing and banks already in need of capital, there is likely not going to be any other lending going on for a while. This means banks’ ability to generate more revenue/earnings is going to be severely handicapped as sour loans make up a larger and larger percentage of their portfolios.

4. From what I’ve read, it seems that the actual Citi number, for capital to be raised, is between $6 billion and $10 billion. This puts their capital needs at $15 billion to $19 billion, since they are selling assets to raise around $9 billion, which is counted when considering the amount of capital that needs to be raised (according to various news stories). Interestingly, this is 44% to 55% of Bank of America’s needed capital. This paints a very different picture of the relative health of these two firms than the “common wisdom” does. Granted, this includes a partial conversion of Citi’s preferred equity to common equity.

5. I see a huge correlation between under-performing portfolios and a bank trying to negotiate it’s required capital lower by “appealing” the stress test’s assessment of likely losses in both the baseline and adverse scenarios. As I’ve talked about before, not all portfolio performance is created equal. Citi has seen an increasing (and accelerating) trend in delinquencies while JP Morgan has seen it’s portfolio stabilize. So, for the less-healthy banks to argue their losses are overstated by regulators, they are doubly wrong. It’ll be interesting to see how this plays out–for example, if JP Morgan’s credit card portfolio assumes better or worse performance than Citi and Bank of America.